“Reclaim power and agency with music” – An interview with Asifeh & Firas Shehadeh

You both have roots in Palestine. How did you first meet?

ASIFEH: I was following Firas and his brother’s rap project Torabyeh around 2010. I was virtually in touch with his brother Ahmad (Kazz) and later met him in Jordan. He took me to the Darat Al Funun art institute in Amman where Firas was working at the time. We met there briefly and didn’t see each other for a long time afterwards.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: I am from Ramleh, Palestine, I was born in Amman and grew up between Saudi Arabia and Jordan. I moved to Vienna in 2015 to pursue my studies at the Academy of Fine Arts. By that time, I was already familiar with Abboud’s work, particularly his work with Ramallah Underground. However, it wasn’t until my brother Ahmad put us in touch.

ASIFEH: I was born in Vienna and grew up here for the first nine years of my life. Then, I moved with my family to Ramallah in Palestine. After I finished high school, I came back to Vienna in 2004, until I decided to move back to Ramallah around 2011 and returned to Vienna in 2015.

“Discovering hip hop was a transformative experience”

You started out with Hip hop, right?

ASIFEH: Thanks to Hip hop, Firas and I connected. To me, Hip hop was not only about the music, it was also a community and a way for different creative minds to connect and jam together. Even though I was a fan of other genres such as punk and metal, Hip hop was the genre that represented my thoughts and words best at the time — it gave me the opportunity to say so many things in just one song, and the beats hit hard and drove the message and emotions across.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: Discovering Hip hop was a transformative experience for me. I was introduced to the genre by my older cousins and their friends in the camp, who exposed me to the music of the Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep, and Nas. I understood that those musicians, just like us, lived in a similar reality, they reclaimed power and agency with their music. Hip hop is their way to express themselves artistically, politically, and socially. This revelation opened my eyes to the power and universality of Hip hop.

The attitude really clicked with you, I guess.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: Absolutely, there was an instant familiarity to it, even though I was into other music like traditional Palestinian music and then later on punk. Hip hop is a culture that encompasses all these ways of expression and energy somehow.

“The internet played a huge role in the Arab Hip hop movement at that time. “

Abboud, you started Ramallah Underground in the 2000s, a Hip hop project with other people from Ramallah. What made you start to speak up initially?

ASIFEH: Initially, I didn’t have serious plans to make music, I only experimented with it after getting an electric guitar and playing with it on Fruity Loops. Then I met Muqata’a, who I co-founded Ramallah Underground with, in high school. He was doing Trip Hop at that time. We hung out and came up with the idea to put out something meaningful together. That was during the Second Intifada. You have to imagine: There were Israeli occupation tanks everywhere, snipers on the roofs, F16s and Apache helicopters were dropping bombs, we had checkpoints between all the neighborhoods, and strict long-lasting curfews. So, most of the time we were stuck in our homes and weren’t allowed to go anywhere, not even to school, with the full knowledge that each time you wanted to go out you would risk getting arrested, shot, or harassed by the Israeli occupation forces. We used that time and experience to express the anger and frustration of the reality we were living in, we were, in our way, reporting the news from the ground. Then, after publishing our work online, people from different corners of the world, especially Arabic speaking countries, started to hear it and it took off from there.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: The internet played a huge role in the Arab Hip hop movement at that time. Between the First and the Second Intifada, computers started to become more accessible, and there was the Internet. This was the place to share our music, meet and distribute, especially between Palestinians in Palestine and diaspora.

Over time, you stopped using words and rather started to use abstract forms of experimental music. Where did this shift come from?

ASIFEH: My „traditional” Hip hop phase witnessed a transformation around 2010, not long after the Ramallah Underground project came to an end. During that time a more experimental approach started to blossom in the Ramallah music scene. Parts of the community started doing more weird and experimental stuff. There was also more noise and free impro coming in, a friend of mine even called it Post-Hip hop because we rejected traditional forms and used distorted beats and glitchy vocals. Being embedded in this scene, it naturally pushed and inspired this artistic decision for me to go more experimental, without any compromise and pushing the boundaries of what should and shouldn’t be accepted as music.

“to try and get the machines to speak”

Could you describe that a bit more?

ASIFEH: A lot of my recent work is probably more open to interpretation. There is usually a theme, but there is not always an explicit message. The listener interprets what they hear, especially when the music does not have any lyrics. This shift with a focus on instrumental production coincides with the moment I moved back to Vienna in 2015. Back then, I discovered Willhaben as a place to buy vintage music gear — everything from synthesizers and drum machines to samplers that I never had a chance to get my hands on. A lot of this equipment was made around the time I was born. I just liked to play around with them, getting dirty sounds out of them. That influenced the way I have been working, to try and get the machines to speak. It’s about taking devices as they are and accepting the sound as it is with all its imperfections.

It’s interesting that you reference so much analog gear when your sound really refers to a digital era, really.

ASIFEH: For me, it has always been a combination of analog and digital sources. I was never really strict about what to use. All gear is just a means to an end, what mattered more was the resulting outcome and concept. Firas and I also produce music on our iPad these days, which is completely digital.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: This is perfect because it allows me to take care of my newborn while drafting ideas and working on new sounds on the couch. However, what truly matters in this process is the approach, story and concept behind the work, rather than the equipment, which I often find distracting. I find inspiration in internet culture, I work with sampling content and sounds from platforms like YouTube or TikTok. In fact, I have even moved away from field recordings, as I feel that there is nothing new to capture in reality, everything is recorded. Instead, I work most of the time with pre-existing materials, regardless of the origin.

“our work is greatly shaped by the impact of technology, politics and digital aesthetics”

I was more referring to the feeling I get looking and listening to the music and graphics you add.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: I find that our work is greatly shaped by the impact of technology, politics and digital aesthetics. However, it is not stuck in nostalgic influences, but rather a vision that stems from our own personal experiences. A prime example of this fusion can be found in my latest album, „Sharqan Hatta Al Maut”, where I blended primitive sampling techniques with AI prompts. Through titles, sounds, and visuals, I direct the listener on a journey that transcends time into space, allowing them to immerse themselves in a sonic landscape.

“to imagine undoing European colonialism in Palestine”

On the cover one can see two white horses galloping through something that appears to be an animated oasis.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: Yes, the idea behind the album is to imagine undoing European colonialism in Palestine, drawing inspiration from various sources such as personal stories passed down through generations, the Palestinian captive movement, literary works by Palestinian authors and sci-fi elements. It’s kind of like Akira but from my standpoint as a Palestinian. And of course, horses have a lot of symbolism in Arabic culture as a whole and in Palestine in particular, resilience, power, dignity and speed.

Can you elaborate on this?

FIRAS SHEHADEH: Despite possessing one of the world’s most advanced military arsenals, the Israeli colonial rule in Palestine has been unable to decode the people and the land they occupy, even after 75 years of the ongoing Nakba. Their sophisticated killing technologies have failed to crack the essence of the Palestinian people and their connection to their homeland. Based on that, my strategy is to challenge colonial algorithms by embracing life as an uncomputable subject.

You both have worked together on various occasions, is there a vision that you share?

FIRAS SHEHADEH: We have a collaborative approach in our respective solo projects, extending beyond the realm of music. For instance, when I am working on a new film or video work, I would share the script or the final project with Abboud to get his feedback. Similarly, Abboud involves me in his creative process by sharing his new albums or tracks for feedback. We have collaborated on joint projects where I produce video work for his music or he helps me with sounds for my videos. This mutual exchange of feedback and support, results in a more refined and impactful artistic output. I think what makes these collaborations possible, is that we share a similar vision in regards to aesthetics, sounds and images.

You started producing music relatively late. Why?

FIRAS SHEHADEH: I was involved in music production before I started releasing my solo projects, but I was mostly in the background or in very small DIY improvisations. I think I didn’t produce music earlier because I was more interested in sound design and edits, I am more interested in the unmusical. Abboud was the reason for me to start releasing my music somehow, as I would share with him beats and sounds just for fun and then one day he was like, yo this is good, you should release it. In the beginning, I was doubting if anybody wanted to hear my stuff, but I kind of didn’t care much, I was just simply sharing stuff I like. Eventually, we started doing music together in 2017. The first song was done in like half an hour.

ASIFEH: That’s why I always enjoy working with Firas. We get things done in a very short time. We talk about it. We record it. We shoot the video. That’s it. I have never worked with anybody who makes decisions on the spot like Firas. It reminds me of the vibe we have in Palestine. We have a creative space there, where we give constant feedback and motivate each other. Firas lets me have that in Vienna — at least to some extent.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: I was lucky to find Abboud in Vienna. Even though we lived through different experiences, we share specific ones. Most of the time, we are not making music when we meet. We talk, whether about an upcoming exhibition or a new book or the falafel we tried yesterday. As soon as we feel the urge to produce, it goes really fast — because we have prepared for this moment all along.

ASIFEH: Sometimes it feels like it’s coming too easy. There is a multilayeredness to it, though. it’s the music as well as the title and the aesthetics.

Do you want to share something you love about each other?

ASIFEH: Before the music business part comes our friendship. We understand each other. Apart from that I really appreciate how Firas puts things into words. I normally don’t talk so much other than my own lyrics, I guess. When I am hanging out with Firas, I don’t need to because I am constantly learning.

FIRAS SHEHADEH: To be honest, it’s more than friendship, it’s like family. And even if Abboud doesn’t talk as much as me, he really slaps it when he does — not with big and fancy words, but with grounded real life experience.

Thanks much for the interview!

Asifeh

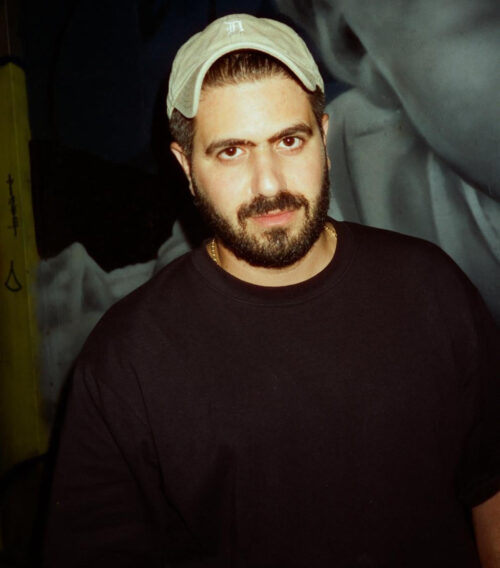

Firas Shehadeh