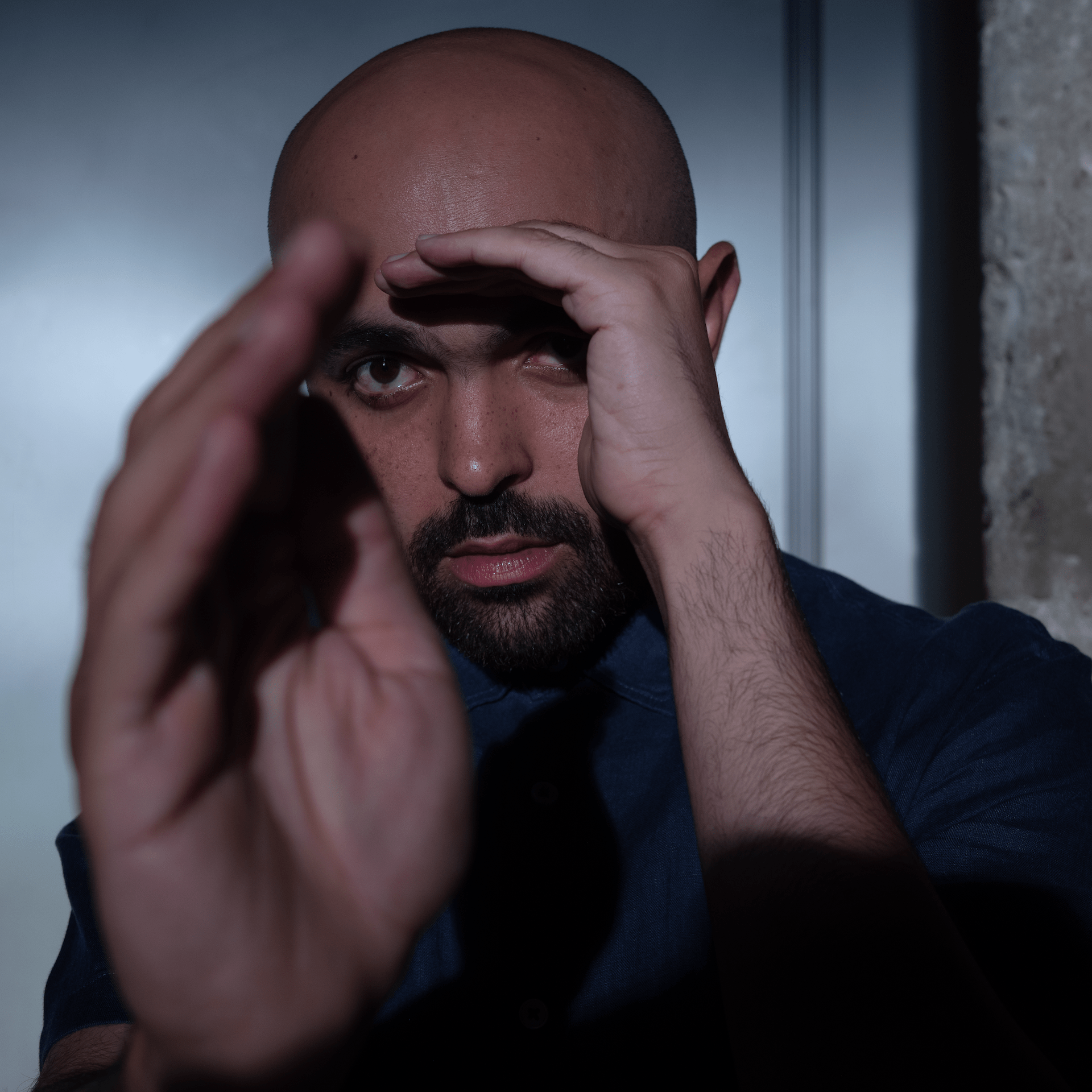

“I felt like the room was full of spirits” – In conversation with Abdullah Miniawy

Abdullah Miniawy’s exceptional art found me for the first time last year. It was his collaboration with Copenhagen-based artist HVAD – “Notice a Tiny Scratch for the Blue Behind” [2022, ULLLUI]. I remember being drawn to it by the cover artwork: a person riding a donkey, crossing railway tracks in a foggy, rural landscape. The earthy colors were in harmony. It was a strong, auratic photograph. When I heard the songs that accompanied it, the voice of Miniawy, I imagined the singer to be a 60-year-old man, someone who had experienced much in life, endured pain, and been marked by destiny. Like the figure riding through the fog, possibly.

A few months later, Shoot The Engine [2024, Amphibian Records], his collaboration with Carl Gari, was released. When I listened to it, I was immediately struck by its intense beauty. Even though the lyrics were in Arabic, it felt as though I could understand the message, which carried a deeply political meaning for me. In all its beauty, I heard trauma, misery, oppression, fear, anger, desperation, and revolt.

Eventually, I did some research on the person behind these songs. It was quite a surprise to discover a 30-year-old, Paris-based Egyptian singer as the author.

Miniawy’s name kept reappearing in various contexts over the course of the year, until he finally came to perform in Austria. I took the opportunity to see him twice – at musikprotokoll in Graz and at Dishes in Vienna. The performances were stunning, expressive, and intense. They resembled a believer praying. In Vienna we finally managed to sit down for a long conversation about his roots, the magic of his voice, the ghosts that haunt him, and diasporic consciousness. It was December 2024. I pressed record in the middle of the conversation…

“We’re trying to decolonize the music industry in a way”

… yeah, that’s right.

The labels try to make more money. It sucks because there’s no money. There’s inflation, there are problems in this world… And they want to eat artists alive. They are asking to get into publishing too. Like, to sign a label deal, you have to sign a publishing deal. So as an artist with a release, you can’t make much money anymore.

You can, if you’re in control—like on Bandcamp.

Yeah, but I think I have to say it’s dead now. People over-consumed it.

You think so?

During COVID, yeah. Now, you don’t get money at all. I look at all the records I released, and it’s peanuts—not even enough for sandwiches.

As an idea, Bandcamp is great. But in practice? No.

So what’s the idea behind the label?

My label PPL Songs actually submitted for a fund from Lebanon. The idea is to release all my music through it—and also release diaspora artists.

We’re trying to create a deal where artists are co-producers from the beginning.

What does that mean?

It means they also have to invest, in a way. So, when they invest, we get an automatic split: 70% to the artist, 30% to the label. I want to push more to the artists. I also want to work with lawyers to track all released materials.

Like, for example, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and others—so many big names who basically sold lifetime or even posthumous rights to labels.

We’re trying to decolonize the music industry in a way.

What’s the name of the label?

It came from a hater on Instagram! There was this CairoScene magazine that put me on the cover, and someone commented like, “Oh my God, there’s not one song that people can listen to!” He said it in Arabic: “مفيش ولا أغنية زي أغاني الخلق,” meaning something like, “There’s not a single people songs.” So I just named the label “Aghani el Khalq”—which means “People Songs.” I loved the comment.

“I didn’t want to just be ‘a rapper’.”

When are you kicking it off?

I already have two records planned for next year.

The first is with Maurice Louca. It’s almost finished. We had a session in December or January. I was working alone by the end, since Maurice had already done his part. It’s going to be a big thing. Maurice is well-known and respected, and we’re touring. Every time we send a snippet, people are like, “Get me this.” It might be his first “happy” record. I did my first dance-floor love music—Egyptian beats, Arabic broken beats, Yemeni beats, some rai…I even have this big section of raï music

Anyway, Maurice also encouraged me to make the label. He said, “I don’t want to work for five years and then give my copyrights away.” He was really pissed. He’s been in the scene a long time, and he said, “Let’s do it in the family.” That pushed me. He’s important to me. He was the first to offer me a MIDI keyboard.

I’m tired of the same narrative: “Carl Gari, Le Cri du Caire.” There isn’t just one way to listen. There are many approaches. In France, the press is still relatively high-quality, but they always run the same story: “The icon of the Egyptian revolution.” It sells. But that’s one of the main problems. Even my previous Le Cri du Caire producer is selling this narrative so hard.

There’s also an exotization coming with it.

Exactly. He doesn’t know.

He’s sometimes so hard on everyone—especially himself. All I’m asking for is: Can I travel less? Can I have my dinner time? Simple things. But since I started my company,” you know? Before, it was like: “You’re sick? Take cortisone and play.” I did that for years. But now it’s over. I can’t anymore.

When did you start getting active in music?

I was always curious, to be honest—about how the industry works, how the structure behind it functions, all the details.

I actually studied law, international law, and that helped me. I had to look at contracts, write most of my own deals, and I got screwed over a lot. For example, I worked with MoMA PS1 in 2012. I made 14 soundtracks for them and got 900 euros—for a lifetime license. I didn’t need to study law to realize that wasn’t okay.

Yeah, of course. But I guess at the time, you needed the 900 euros?

Exactly. But the way they played things—it always felt a bit stinky, you know?

I started releasing music when I was 16.

What was the style back then?

It was spokenwords—but not really. I started by singing a bit. I realized that pure rap poetry wasn’t always attractive to people. So I wanted to break out of that—I didn’t want to just be “a rapper.” I started singing in the chorus sometimes, or even in the intro. It was classical Arabic rap, so it got a good reception, and we were welcomed in the rap scene.

Later I dropped the beats, kept the slam, and started singing more.

When did you start seriously singing? Like actual practice?

When I had my first smartphone, I’d say. I was young—it was even before 16, when I had access to a tool to record myself. I don’t remember exactly when. And that’s when I started recording and listening to myself.

“My mom used to sing all the time”

So you were taking lessons?

Not at all! It was totally natural. And honestly, I think that’s why it worked out. My mom used to sing and improvise lyrics all the time in the kitchen while she was cooking or working around the house. She’d improvise constantly—crazy stuff! She is not a professional singer, but just for fun. I’d hear her and was just soaking it in.

My dad, on the other hand, was very strict. Strong personality. An erratic teacher, very structured, very harsh about order and discipline in the family.

Combining both of those energies made me who I am. It also helped me enter professional life and—somehow—actually fulfill nearly 90 shows this year. That’s almost over now, and honestly, I’m happy. I don’t know how I said yes to all of them…

So you’re a disciplined worker?

Yeah exactly, I’m disciplined. I work like a regular person. I start at 8 on Mondays. I’m excited to get going. I put on the radio, make a coffee, log in. I organize meetings with friends, spend time with my band or collaborators. In Paris it’s easier now—I get invitations to all kinds of theaters and events. So I’ll take friends with me, go listen to music.

And on weekends?

I play board games sometimes. The last one was a French game—amazing. Five players, each with a different character. And behind us is Charon, from Greek mythology—trying to eat us! There are rules, you have to run to a boat… then we drink beers—it’s awesome.

Sounds fun!

Also, I have a laser tag appointment on the 29th. Not sure

“I’ve had no formal singing education”

Your voice—I’m really fascinated by it. Do you practice every day? Or how do you keep it in shape?

It’s kind of taken care of just by performing a lot. Playing live keeps it in shape – that’s the real practice, that’s where the training happens. Sometimes your voice is rusty – you warm up backstage, then you go on, and after two songs, it starts opening up. Also, I’m not a big drinker. I don’t mix alcohol with anything. You can hear it in people’s voices when they do. I smoke, but even then – I don’t go crazy. So all that helps.

I’ve also been really into sports since 2017 – or maybe 2016, when I moved. I do sports sessions once or twice a week, and I never stopped. If I skip it, I get so depressed. And now I’ve added weights, crunches, stretches – this was about three years ago. I do that twice a week too. So yeah, I have this healthy side.

But did you ever take private singing lessons? Or go to music school?

No, never. I’ve had no formal singing education.

That’s wild. It’s just talent and ear?

Yeah, it’s mostly listening. What I do is loop things – loop myself, over and over.

That’s definitely your structure.

Exactly. But what shapes the character of the voice is more… I don’t know, maybe strong ears? Like, if I hear a car sound, I can repeat it. I listen closely to everything, and then I try to push myself in that direction.

I never, ever tell myself something is impossible. Even far from music – I never say, “This can’t happen.” I don’t limit myself. I try to stay positive in everything.

So yeah – practice is there. But I’m still trying to break it all down. It’s a lot of studio sessions. A lot of listening. Looping myself, writing things down. And I try to change my style from time to time. I have a ton of unreleased stuff – things I just keep for myself. But they all come together in those moments on stage, when I’m improvising. You pull a melody from over here, another one from over there, and it becomes something new in the moment.

“I never, ever tell myself something is impossible.”

Would you say your main inspiration comes from the Arabic region or would you say it is diverse influences from all over?

Well I love church music. I love organs. I listen to a lot of that. And a lot of composers who work around what you might call “contemporary church” sound – like Arvo Pärt, Peter Schat from the Netherlands, Peter Michael Hamel from Germany. I love all of them. I even know some of their instrumental tracks by heart because I’ve listened to them so many times.

But also – I listen to the Quran. I listen to Sufi music from Egypt, to wedding music from Egypt. Then I’ll switch and go into a full rap phase – write rap texts, follow the trap beat. I’m full-time on this. I don’t really stop.

“It was the Egyptian revolution that showed me how powerful words can be.”

What do you think draws you to sacred music—or even, I don’t know, spiritual or ritual music?

That’s a really good question. I think it was the Egyptian revolution that showed me how powerful words can be. When you see how words can move people—how they truly have impact—it starts to feel like you’ve been given a superpower. And maybe that superpower is inspired by God—if God exists. Or maybe… maybe we are the gods. Either way, I feel like I’ve been given this gift, and it’s still driving me. It’s fueled by something I don’t completely understand. But I know I have a role to play in the world. I’m part of it.

Sure, but you could’ve chosen to be an opera singer, for example. You could have followed a completely different path.

Well, even opera still has that divine aspect to it. But you know what’s funny? People always think I’ve had some kind of traumatic experience because of the way I sing. After a concert in Copenhagen, someone told me, in a very kind way: “You should see a therapist—it’ll help your art.” She heard so much pain in my voice that she assumed I had gone through something very dark. But it wasn’t about that at all. What I’m doing isn’t about trauma. It’s about channeling. It’s about opening this door and allowing something to come through. Because to me, the brain isn’t entirely ours. I think of it more like… you know those airport parking slots for airplanes? That’s how I see it. My brain is a place where thoughts land. And when things are aligned—when everything clicks—these words just come. Sometimes it’s just a moment of silence. You’re alone, and suddenly words appear. Sometimes they come in dreams. I’ve even translated my dreams into poetry. And then it’s weird that an only 19 year old had an impact on the whole region.

I think part of why I gained respect in Egypt—especially from artists, activists, people from the revolution—was because we didn’t care. We were just… communist in spirit. We never cared about fancy packaging. Vinyl? That’s a new obsession. Back then, we didn’t care about pressings or waiting a year for mastering and mixing. I always had this feeling: “I’ve recorded something. Now I’m releasing it. Online.” People interacted with it, and then they came to see me live. That was the only space where my work really existed. So it had nothing to do with this Western idea of “the perfect album.” Honestly, I think that model kills spontaneity. It kills the revolution. Let’s say we’re facing environmental collapse, right? If I write an album about it, it won’t come out for another year or two—because of production cycles. By the time it’s out, we might all be extinct! It’s the same with human rights, or any urgent topic. Music can be a preaching tool. It’s not just for fun.

“What I’m doing isn’t about trauma. It’s about channeling.

So would you say your channeling words as well as music?

Yeah—and it’s changed a lot over time. In the beginning, it was all about words. I was speaking directly to the audience in Egypt. But in the end, I started to hate it. I couldn’t sing anymore—people were just screaming my lyrics at the concerts. I’d come out and say, “As-salaam,” like the start of salaam aleikum, and the crowd would shout it right back. It became a thing. Most young men in Egypt still use that line: “As-Salaam!” And I made it into something real. It’s funny. But eventually it became too much.

Why did you leave Egypt, then?

Well, it’s complicated. I did have this big success and influence, and yeah, there was power in that. But at the same time, I didn’t feel safe. And it wasn’t just personal danger.

It’s an oppressive regime.

The government is oppressive, and people are… kind of lost. But they can open up—if you speak to them in the right tone, in the right way. We talked about this at the bar: how our countries have this insane hospitality toward strangers. We love outsiders, in a way that’s intense. But I think Western media really exploited that. They took all our beautiful qualities—kindness, sharing, physical affection, communal culture—and twisted them into something scary. So when people hear about Egypt or the region, it’s like, “Oh, they’re going to harass you,” or, “They’re going to assault you.” But no—they’re just overwhelmed by your beauty, your presence. They express it loudly. And then someone raised in a Western context sees that and panics. It turns into a clash of cultures, but it’s actually a misunderstanding. Most of the Europeans I know who go back and forth between Europe and the region—if they can respect the culture as it is, with all the layers of religion and history, while keeping their lives in Europe—they become the strongest, most balanced people. I trust them the most.

I think society is ready for transformation. And I think the term “Arab” in Europe—it’s strange. I never even heard it used like that until I got here. We are humans not elephants.

At first I was like, “What’s wrong with France? What’s this label?” It was like being shoved into a category that didn’t reflect who I was. When I arrived, I was so bright. I had this light inside. Maybe I was a lighthouse—I had that much energy. But over time, people started dimming me down.

Like, you’d meet someone on the street, say “Hey, what’s your name?” And they’d be like, “Oh… wow… that’s beautiful.” And slowly, those kinds of reactions make you turn it all off. You dim down. I think the media has worked hard to separate people. And it takes different forms—sometimes it’s war, sometimes it’s women’s rights, sometimes it’s… Disqualifying people, LGBTQ… open the borders, give everyone the same right of mobility and with time, you’re going to create a dialogue if we are able to immigrate to every where the term immigrant will vanish by time.

“When I arrived, I was so bright. I had this light inside.”

Sometimes my mom calls, asking “How’s France?” And then I’ll say something like, “Ah, not good. I checked the news, and the far-right is growing.” And then she is like, “What do you mean, ‘far-right’?” Because the truth is, a lot of these problems are created within Europe. And they’re not even properly translated to the outside. In the Arab world—ugh, I hate that term by the way. I hate being called “Arab,” because we’re so different in so many ways.

Yeah.

But I had this dream when I came to Europe: that I’d help correct things, lead something, offer something different. This platform of “human rights” and “diversity”—the way Europe promotes it— I thought I’d find space there to build something new. Back in Egypt, I was anti-religion. At 20 years old, I was performing in Tahrir Square—writing lyrics against God and Islam. And people loved it! They were ready. They wanted change. They didn’t agree with everything I said, but they respected that I was opening up a conversation. Together, we became powerful. Then I came to Europe thinking I’d continue that mission—but after two or three years, I found myself put into the same box as everyone else.

The same person who would criticize Islam from a deep, personal place—now looks at the problem in Europe and sees that the people labeled “Arabs” here are the most silent, the most powerless. They don’t fight back. Most of them just want to live quietly, unnoticed. And because of that, they become a sad minority. And with any minority, I’ll stand beside them—through my art, through my music. But what’s strange is: I’ve found myself defending Islam here. And I never wanted to. I’m being pushed back into that role. Sometimes my friends joke that I have right-wing tendencies. And yeah—maybe I do sometimes. But let’s talk. Let’s have conversations. That’s what I’m trying to do with my work.

So do you feel like you’re being forced to mediate between cultures now? Would you say that living in Europe—rather than in Egypt—has influenced the music you’re making now?

I’m haunted by European ghosts now. Frustrated ghosts. They come to me. And I’m channeling that too. The sounds I hear now are different. It’s clear in the music. So yeah, I’d say I’m in between. I absorb everything—I’m like a sponge wherever I go. That’s part of being an artist, I think. Absorbing the world and then transforming it.

“At 20 years old, I was performing in Tahrir Square—writing lyrics against God and Islam.”

Especially when you’re performing for Western audiences who might not be familiar with the vocal techniques or traditions you’re using—do you often feel exotisized?

Sometimes. Sure, some people come with expectations. I’ve performed over 700 concerts in the last eight years. That’s a lot. I release one or two records every year. I’m constantly creating, constantly documenting. And I’ve maintained a really high standard, especially in the use of Arabic. I don’t think I’ve ever delivered a grammatically incorrect Arabic poem on stage. Because in the end, people understand emotion—whether they speak the language or not. They know what it means to cry, to laugh, to feel joy or pain. That’s what I’m triggering in them—something universal.

But yeah, sometimes it’s wild. I’ve played shows in right-wing cities, even at festivals organized by right-wing parties. I’ve sat at dinner tables with them. But then I get on stage, and by the end of the show they’re clapping and jumping out of their seats.

So you become the “good immigrant,” the exception?

It’s not about being “good” or “bad.” It’s like ants, you know? Or animals—we all have different roles. In this world, not everyone has to be the same. We need to accept that people are born with different talents. There are gifts. Specializations. Just because music is trendy doesn’t mean everyone should do it. It doesn’t mean carpentry is lesser. I can’t even fix something with my hands—but I know how to use my voice. That’s who I am. That’s how humans are built—different, beautiful, specific.

Yeah, but that’s the beauty of art and music, right? It can reach people no matter where they come from.

Exactly. That’s the power of it.

And when you say you’re “channeling,” do you ever think about what it is that you’re channeling?

The more I try to describe it, the more it escapes. I’m sorry for it—but I really don’t know how to explain it.

Maybe it’s some kind of creative force?

Call it that, sure. Or something unknown, untouchable. We can call it “creative force” if we need a name. It’s like in science—you go into the garden, pick a flower, and try to analyze it in a lab. But really, maybe you should just look at the flower. Study it as it is, where it is.

Yeah, but it does make a difference, doesn’t it—what kind of approach you have as an artist? If you say you’re channeling something, it implies there’s something greater than you. Maybe not above—maybe around.

I just know that when I nurture that voice inside me—when I feed it—then I get into this state. I start translating what I hear. It could be a sound, a thought, a temperature, a smell.

Words too?

Yeah, words too. I start translating whatever’s in my heart, in my head, even in my feet. It’s a weird state to be in. You’re getting dressed, thinking, “Okay, I’m gonna look good tonight.” You try to leave the house… and suddenly it hits you. You fall back into the studio. You can’t leave. It’s happened to me many times. And the results are usually the best poems or songs.

Like “Heaven for Non-Believers”—the track from Nigma Enigma. I had two weeks in Malmö for a residency, and in the first week I was completely alone in the studio. Every day I was there, from morning till night. But by the fifth or sixth day, I was spiraling. I thought, “You hate everything now. You can’t express yourself anymore.” I was being so harsh on myself. So I recorded something quickly, just to have something. Then I went back to the hotel and kept listening to it in a loop—as punishment. I told myself, “This track is bad. You’re gonna listen to it all day.” From 8 in the evening until 2am, I walked, ate, had a beer—still listening.

And?

At some point, I started to feel it. I started to love it. The track got under my skin. So I ran back to the studio. It was past hours, and the building was locked down. I broke the fire alarm to get in. I set everything up—mic, headphones, all of it. And I recorded one take. That was “Heaven for Non-Believers.” I never changed a word.

Wow.

Yeah. And after that, everything flowed. The whole album came together day by day. That moment between spontaneity and delivery—it’s very thin. If you miss it, it expires. Magic expires. And when I finished that take, I got chills. I started to feel scared.

Why?

Because I felt something behind me. Not one presence—many. Ten, twenty… maybe more. I felt like the room was full of spirits. I could feel breath on my back. And I ran out of the studio. True story.

Are you a spiritual person?

I followed Sufism for a long time. And now, I think the way I practice is through words. The power of words—it’s real. Everything we write becomes true in some form. The world we live in is built on that. Even governments operate because they understand the power of language. Words are everything.

But words work differently than music, right?

Music is instinctual. With words, there’s more reflection, more structure. Words can be edited, rewritten, restructured. But also… sometimes you just let them come out raw. That’s what I do when I write. I don’t edit too much. I don’t overthink. It’s a kind of channeling too, I think. Sometimes it just flows—like I’ll write one line, and ten more come immediately. Then I go to sleep. Later, I might revise a little. Try to follow some rhythm or internal structure. But I keep it mostly how it arrived.

So the words come before the music?

Not always. It depends. In the beginning, it was definitely the words that came first. It was almost prophetic, sometimes. I’d confront something I was seeing or feeling, and words would just come—strong, complex poetry. Even people deep into Arabic literature were like, “What? This can’t be from an 18-year-old.” But it was. That’s how I started. Later, I started receiving melodies too. And at first, I pushed them away because I wanted to be a writer. But then I realized: melodies help communicate the words.

Why?

Because the audience doesn’t speak Arabic. So the music became a tool to transmit the emotion behind the words. At first, I struggled to accept that. But now, I see that melodies can be like passive poetry. They carry meaning—even when the words aren’t understood.

And now you’re writing music for multiple voices too, right?

Yeah. Now I compose for two, three voices—even more. Like with the vocal ensemble from Corsica—A Filetta. Eleven singers. Polyphonic structures. I composed music withfor them. I wrote lyrics too. And lately, when I receive melodies, the lyrics are built into them. That’s a new phase for me. It’s like my creative brain has evolved. Now the words and melodies arrive as one piece. It’s like a muscle I’ve trained. And now it’s functioning in this new way.

When we were talking yesterday, you mentioned your posture on stage—how you perform. You said something about a kind of prayer position. And it was really striking—it had this aura, like it was reenacting a kind of ritual. It reminded me of liturgy, like Christian prayer and singing. It felt very universal.

Exactly. That’s the feeling I want to reach.

“The melody becomes the vessel.”

And in a Western context, where the audience doesn’t understand the words but can feel the music—do you think the melody alone can carry the meaning?

Totally. The melody becomes the vessel. That’s how I judge whether it works or not—it’s intuitive. I have so many ideas on my computer. But not everything gets released.

“I’m very critical with myself. Maybe too much.”

So how do you decide?

It’s instinct. The artist inside me knows. There are some things I love so much—even from other artists—and some I just can’t connect with. It’s not about technical quality. It’s a gut feeling. There are tracks I’ve made that I can’t even listen to anymore. Not because they’re bad. Just because something in them doesn’t feel alive anymore. I’m very critical with myself. Maybe too much.

Let’s keep talking about this outside. Want to grab a cigarette?

Yeah, they’re right here. You can try this one if you want.

It’s really interesting, though…

Yeah…

Abdullah Miniawy

This article is brought to you by Struma+Iodine as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.