Frankie Pizá: Calm down! Being mainstream is no longer a problem…

It was like making a pact with the devil. Being in the same room as other deliberately mainstream people. Listening to an artist who bluntly speaks about reaching the commercial peak. Watching someone, from the back row, speaking about the same philia you have been chasing a few days ago in some alternative establishment.

You could only be thankful because it would have been some bad dream: meeting someone who had gotten to something before you did, to something you had been deeply into already before the public knew about it.

Where many of us millennials grew up, in that space of rampant and snobbish endeavour and consumption, which means identity, the term mainstream was almost derogatory. Something no one ever wanted to achieve; a word that everyone wanted to eliminate from any routines. If it was used it was with the objective to de-catalogise or neutralize any cultural product.

The reason? Distinction. We were servants to scarcity, even if it was illusory–it had always felt better to be one of the first ones to arrive at something. And while we realised that what we had arrived at was already out of the house, we abandoned it as something out-dated.

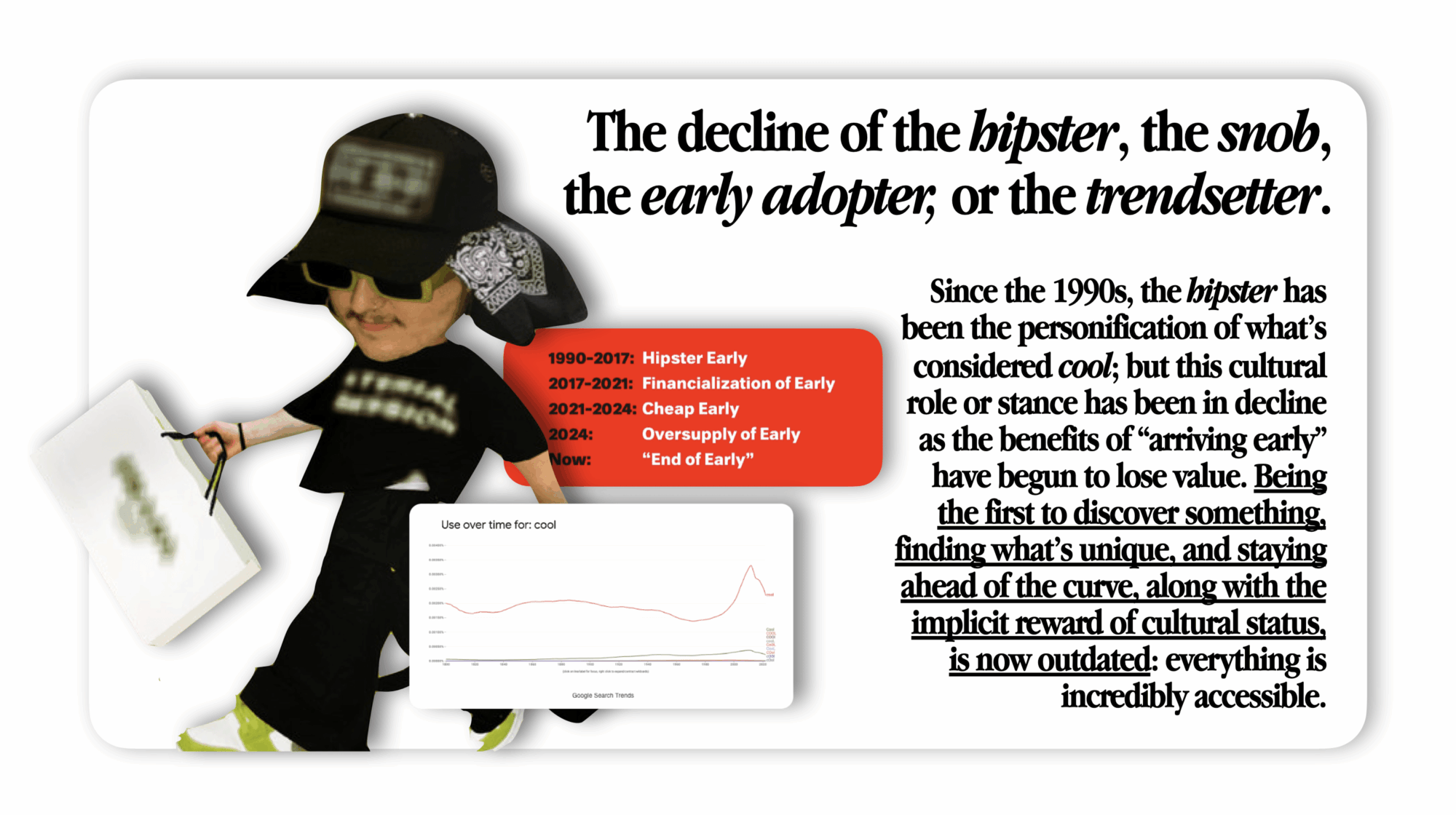

The extinction of arriving earlier and the change in what we understand as gatekeeper…

It was the toxicity and self-sabotage of the now extinct hipster of the 90s and 00s–the hipster preferred to be right before the others and for a limited time only, over being able to monetise their knowledge when something they adored started to find a potential audience. This type of hipster was disgusted by money–they preferred speaking to only two or three people about this over even a faint taste of profit.

Today, some theorise that the lack of these types of roles in our circles and communities has immersed ourselves in an epidemic of bad taste; the traditional gatekeeper, the elitist, the one who kept locked up certain artifacts and cultural currents for his future advantage, gave way to the judges of cool and uncool, those who selected organically (and obviously over certain interests) cultural products above good and bad. Cool was a category on the margins. It was not only what they made that mattered, but also what they silenced.

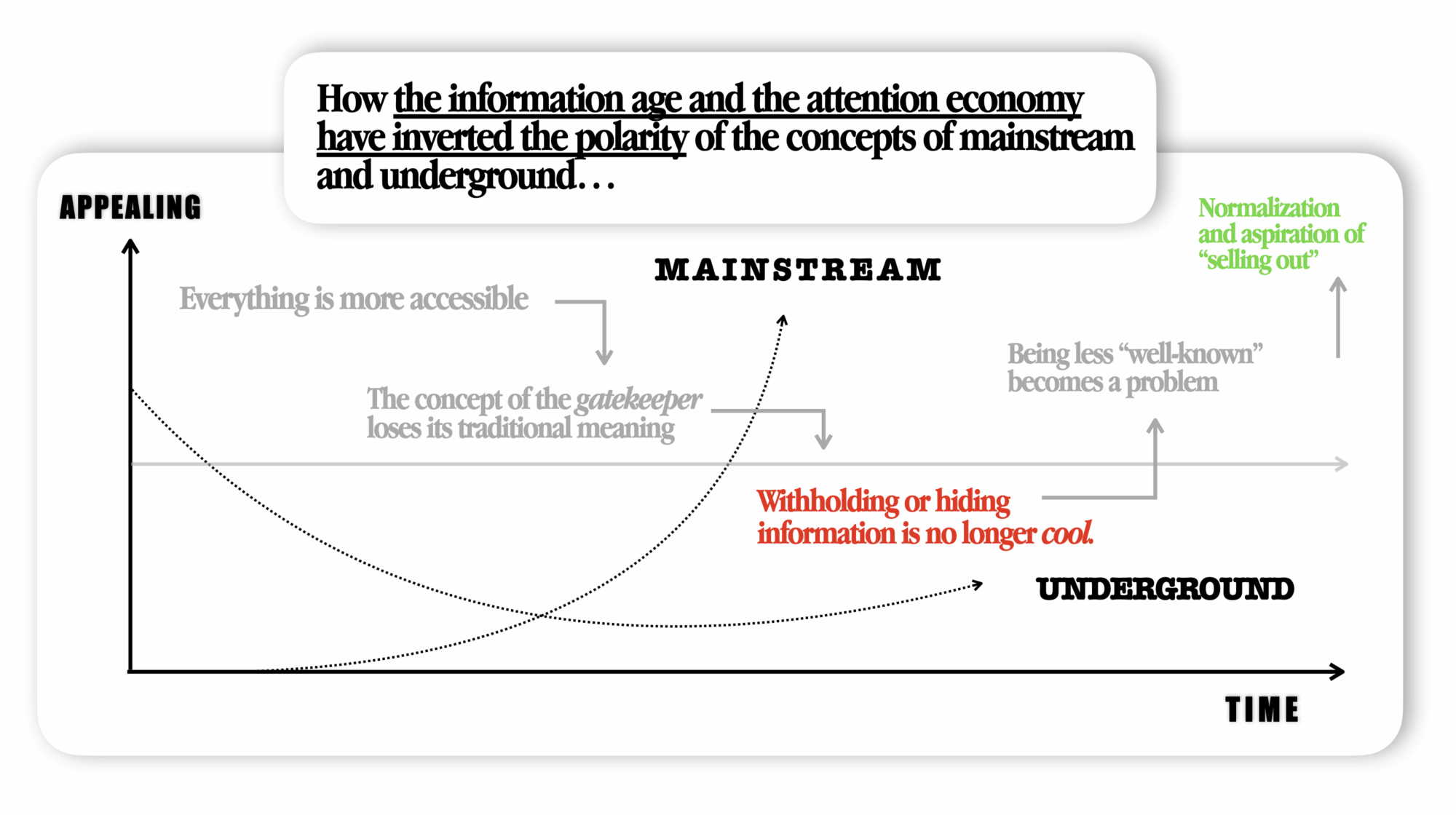

In the realm of the viral, none of this matters.

The internet and the channels of social media levelled out the culture and its more marginal expressions by compressing their meaning and leaving them at their assumptions and visual traits.

Nowadays, cultural currents or products that have less visibility and are less legible cease to exist due to the lack of attention. In the same way, each one of us acts like their own brand and merchandises culture running through us, marketing an ever-changing identity. Today, cool happens 24/7 and it is a direct conversation with our audience.

So what is the point in keeping back information in the age of information?

Moreover if everything we consume is increasingly prey to appearances and abuses signifiers instead of signified, it’s easy to disengage and generate a different sense of belonging than before.

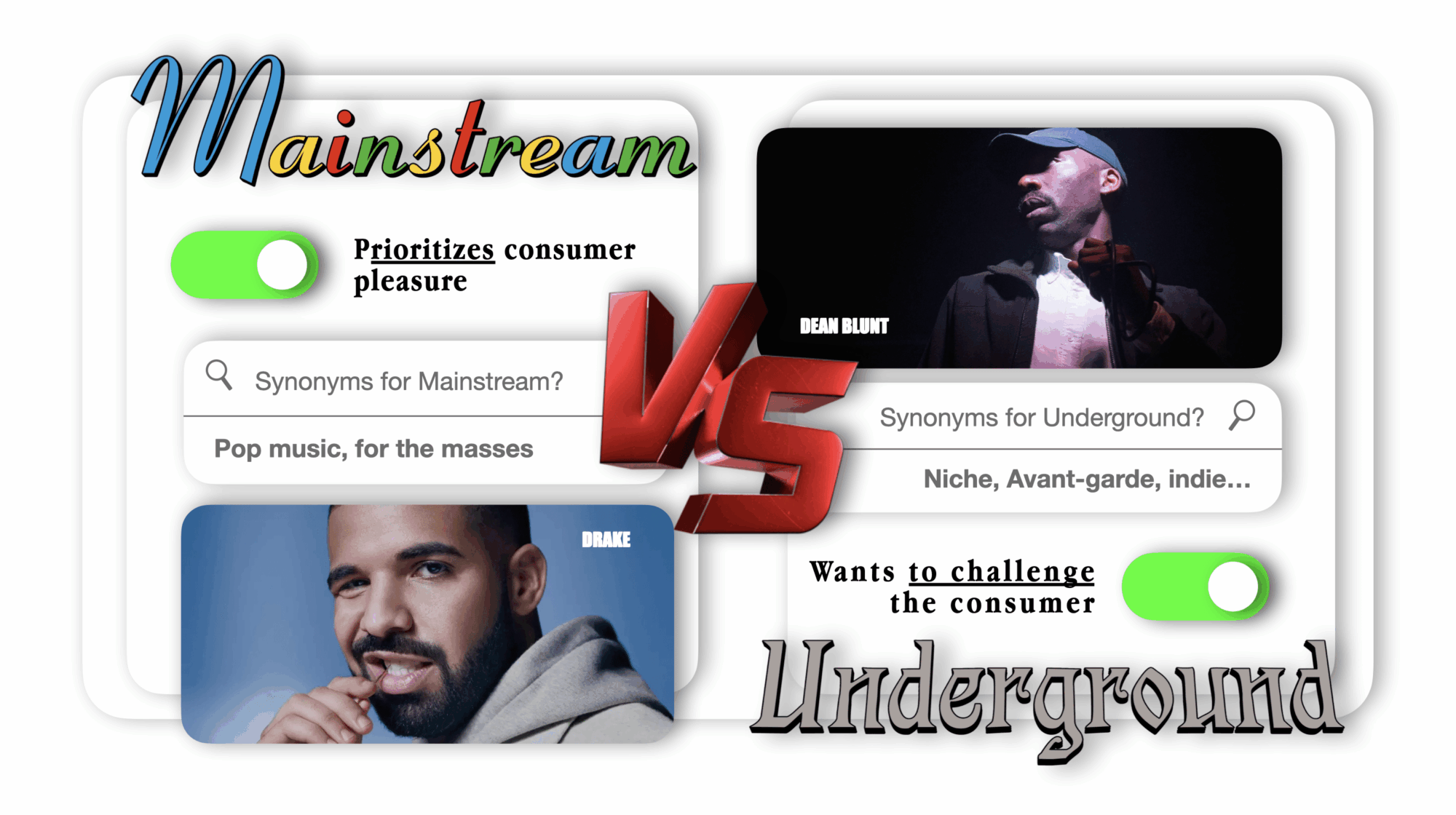

A decaying or non-existing tension. Mainstream vs. Underground

When the language of brands and marketing began to cannibalise our cultural strongholds, going mainstream was an insult.

A synonym for betrayal–everyone wanted to be a star like Prince or Michael Jackson but they wanted to do that by magic, without having to pair up with any clothing or car brand. It was like spitting on your own values in order to have fame and success in the high-speed lane.

It was like assuming that what you did, whatever it was, was a consumer product. Like Elvis Presley or the Rolling Stones–music for the masses, popular music, pop. Products that sought the instant pleasure of the consumer.

The era in which the idea of pop started to spread is also an era in which musicians of certain renown, for example, were able to make a living off the royalties from their recordings. Also, why not say it, there was easier access to housing and the systemic inequality of wealth unleashed by capitalism wasn’t as blown up as today.

Not being mainstream was an option, and even if it was not sustainable in many cases and barely brought any income, there was a certain security to pursue our particular mission.

Just as traditional gatekeepers ceased to make sense and hipsters, the early-arriving guardians of cool, desperate and compulsive, no longer have a substrate to operate in. The term underground has taken a turn–like almost any cultural significance in the realm of the viral, it has lost its engagement.

If standing in the way or putting ourselves between something cool and its potential audience is something almost embarrassing nowadays (Are we going to waste the next reel highlighting this new book that we have seen recommended on some Instagram account that we and another hundred thousands follow?) the search for the mainstream a.k.a. a lot of sustained attention is nowadays an objective for which no means should be spared.

Today, being mainstream is a feat, yes, but that aspiration is shared by 99% of people of the digital circuit. This reality invalidates the notion of having sold out, as mass validation and/or the achievement of great attention or virality is the common currency.

Recognition that can be metabolised and transformed into monetisation. Who wants to block the income of money nowadays? The priority clearly is another one–if in the past, financial security was secondary and the artistic-cultural values were a root asset, today avoiding illegibility is almost obligatory.

The flip side of this phenomenon or paradigm shift directly impacts the underground: Does it really exist when everyone who used to be able to inhabit what they do, is gaining popularity and attention? Maybe your narrative is to avoid attention and the story is going against the grain but whatever your content is, it dwells in the same system and it is condemned to the same norms.

I would have never thought, five or six years ago, that someone like DâM-FunK would end up selecting music for an H&M-sponsored event. A producer of integrity. An artist who assured us of “no fads, no sell-out.”

You may still call yourself underground because what you do or where you are does not have a million consumers, but the previous notion has changed. The sensation of cutting-through uninhabited spaces, never heard of and reluctant to popularity, is no longer valid–it has been eliminated by the system.

Something tremendously accessible is something not hidden and therefore easily found by any digger who uses the Internet. With just a few counter-rhythmic manoeuvres we could find what we long to find. What we later are going to pass on to our followers who are helping to make it a little less niche.

And there is an audience for any niche today–whatever we do, we will be validated by a number of potential audiences.

Contemporary Hip Hop culture as a trigger: success as a medium and as an objective.

Nowadays, there’s a tension that permeates almost everything and that is the desperate commercialisation of culture and our identity on one hand and on the other hand it is the search for something that remains authentic.

In rap, authenticity cannot be bribed at all. The success in the 80s and 90s was a consequence of being authentic and real. In no way was it something sought after, but something needed. Some rappers wanted to leave their personal hell and context through their art, through their singles, their rhymes and their cult of personality.

Quickly this sensation was impaired and even if it’s still existing today, it’s something residual and only rhetorical: the rappers of the new century indulged in absolute opulence and possessions. They created a lifestyle in which success was an essential ingredient and not just something secondary.

Owing to the immense promotional machine and the booming audience, rappers traded rap to leave the void for rap to buy a Ferrari and stacking up wads of banknotes in their trailer. What once was a lever to climb up from one class to another or to simply survive transformed into an interchangeable lifestyle.

Mainstream or underground, or both at the same time.

There is nothing underground in a product that seeks to self-market itself and tries to find its way to its customers at all costs.

Any ascribed, or initially subcultural, project finds itself trying to capture followers, in a relatively short time, with some forced POV-video that manifests some conflict.

We have lost the ability to be mystical, to leave space between two things. We have lost the ability to be silent or to let the viewer or consumers be the ones who interpret the meaning.

Your music, for example, can be niche. Obviously it will depend on the person who listens to it and on their context, but it can still be inaccessible or challenging–to propose an unconventional experience. But that can happen while you reach the mainstream: being validated by a large audience.

Arca, for example, is an artist who maintains the ambivalence between both paradigms–their music is still difficult for the average ear but it can star in a campagne of a prêt-à-porter brand. Arca continues to embody the role of a subcultural and alternative agent while never refusing any opportunity to commercialise and make profit.

There are many more artists who, at first glance, maintain this balance between a more niche and a more commercial offer–a way of pleasing more ears, from the most edgy to the most normie.

Even though it is still a narrative that one enters and leaves, a rhetorical layer of pretence of avant-garde that is not really what it claims to be–while the objective might be to increase the follower count and to keep putting make-up on our identity in order to later transform it into commodities or to sell it to others, there’s no such thing anymore as the avant-garde.

Or it does but it is not avant-garde that is quarrelling with commerciality–one that has been completely trapped like the cool was trapped, that went from the counter-cultural meaning to a marketing tool.

⚉ Selling out without selling out by Metalabel.

⚉ The Nemesis Guide to Being Early by NEMESIS.

⚉ In defence of gatekeeping by DAZED.

⚉ “I AM THE LEADER”: Ye in conversation with Tino Sehgal by 032C.

The article has been first released in Spanish via ZONA FRANKA, the substack of Frankie Pizá.

About the author: Frankie Pizá defines himself as a context creator, a position he believes is radically necessary given the context destruction into which platform capitalism has plunged us. He is also a disseminator, influencer, cultural agent, and theorist in new communications, working in multiple fields: from contemporary art to music, his main area of expertise. In the past, he served as creative director at Primavera Sound and has undertaken several entrepreneurial ventures in the fields of music and technology; his current activity focuses on his cultural project FRANKA™️.

This article is brought to you by Struma+Iodine as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.