EM GUIDE: Music without Agency – The struggles of acting in the alternative scene

At the age of the great alienation and dopamine addiction due to short format content dump, creating something that sticks and brings people together can feel like a task for Sisyphus. Promoters and organisers fight for audiences and venues and challenge themselves by finding the perfect date for their release or event. We live in an age when the algorithm of the metaverse dictates the success of an alternative music event, and it sells us the false idea that reaching your target is a token for a successful party. With little to no funding options and safe spaces, culture is pushed into mines, cellars, semi-illegal pubs and private houses. The active players of the scene needed to build resilience and find certain coping mechanisms to work around the silent suffocation of culture and normalised being thrifty over aiming for quality.

As one of the founders of 111records and manager of Family Fast collective, I am constantly seeking successful methods and good practices that could serve as tools to sustain the development of alternative and politically engaged art practices. To find some answers, I asked two active characters from the musical map of Hungary to tell me about their insights and visions on the current situation of the nightlife, the audience, the venues, the funding and many more. One of them is an experienced rider, being in the circle for almost seven years. The other person, on the other hand, is a fairly new but definitely prolific agent who established a sound and a visual language that has managed to break through the frozen lake of Hungary’s alternative scene.

“Várhelyi Valentina: Hi! Who are you?

Gergely Csontos: Hi! I’m Gergő, a 23-year-old autodidact artist and operator of the platform Marmint Agency. I originate from a small Hungarian countryside location called Talfája, but for the last couple of years, I’ve been based in Budapest. I have been making music in the past 10 years by various monikers, mostly with the alias SUTA.

What is Marmint Agency? Where does the name come from?

The Marmint SoundCloud profile was registered around 2014-2015 to archive some of my early works while I was still learning FL Studio. That was the same time I started becoming familiar with the Hungarian experimental music scene and contemporary artists who also used SoundCloud (SC) to find other producers across the country, such as (1) felhasznalo, asvanyviz2, or előd.

By 2023, I’d been pretty active on musical terms and gathered wonderful friends throughout the Hungarian SC community. Right around that time, with these friends of mine, we were already planning to launch something like a small label. Marmint remained functionless until April 2023, when I got the idea to start using the profile as an imitation of a modern electronic music platform, the one you can mostly see in Western Europe. However, my only intention was to upload short guest mixes of my friends and put some of their music out like an internet archive.”

Design for 111records and Mármint Agency collab event by Gergely Csontos

I have known SUTA for two years now and was lucky to work with him many times before. His sound and graphic design journey unfolded in front of my eyes, which I am entirely grateful for and I cannot wait to hear his upcoming release. We have been sharing ideas about the Hungarian music scene ever since we first met. One of these frequently upcoming topics was the question of the ‘Hungarian sound’. In Western Europe and the United States, electronic music found its footing with the emergence of nightlife, and by now, if someone says Bristol, Detroit or Berlin, we can associate it with a very specific sound.

During our talks, I came to the realisation that in the theory of subcultures, music is usually interpreted as a cultural adhesive. Something that is used for oppressed groups to build a community and celebrate together without the pressure of fitting in the society that was created by their colonisers. In today’s political climate, many artists feel the same way. Discrimination against the LGBTQ community and racism are everyday issues in the music industry.

I feel like there are a growing number of attempts to establish tools against systematic oppression and social injustice in alternative cultures. However, division and competition are very much present within the community, hindering its potential impact on mainstream culture. I have been looking into this phenomenon in the past year, because I found it quite controversial that underground artists constantly feel the need to be more visible. How can a community sustainably grow while maintaining its moral and cultural values? Is it even necessary to popularise left-field music?

In search of answers came the idea of interviewing Sándor Kispál (Saskó), who has been working in Gólya for five years now, which is an independently run cooperative cultural centre and club in a gentrified district in Budapest. I asked him about Gólya’s democratic working methods, horizontal arrangement and the current structure of their team to uncover the process of a vision becoming a mission. Demystifying the aura that surrounds subcultures is what makes them more inclusive and accessible. For this very reason, I invite you to take a glimpse into the world of Gólya presented by Saskó.

Gólya, during a larp organised by Family Fast

“Várhelyi Valentina: Hello Saskó! First, can you tell me about your role at Gólya?

Sándor Kispál: Last August, we went through an organisational development and set up the current structure. We established the Gólya Federation, composed of three main productive branches now called member cooperatives. I am a cooperative member with responsibilities on both levels. Within hospitality, I am the coordinator of the Concert Organising Working Group, primarily organising electronic music events on Fridays. Our shifts are relatively non-hierarchical but come with responsibilities. Each position has some responsibility for the evening’s proceedings, but no one’s job is solely to, say, stock the refrigerator with beer all day.

VV: What is your experience working here since you reopened at Orczy tér five years ago?

SK: Gólya is great because it’s a community project focused on how people can cooperate, make decisions, and organise work together. People with individual desires or motivations can channel those within the cooperative. As for me, I started DJing with the PÉNZ collective, which was a hobby at first, but Gólya gave me the opportunity to explore it further, leading me to get more involved in organising electronic music events.

VV: How is it possible that the community has been functioning for so long? In your opinion, how can internal conflicts be effectively avoided?

SK: I think it mainly lies in our onboarding and candidate membership processes. Those who do intellectual work collaborate in workgroups and are assigned to feedback groups. The methodology for this is based on the publication “Giving Effective Feedback.”. A lot of issues can be solved within these assertive and effective frameworks. Additionally, what helps maintain a conflict-free environment is that there are no power monopolies in this organisation. Everyone takes responsibility for an area at a similar level to someone else in another area. We try to ensure that everyone can contribute their ambitions and creativity to a given area, and this is taken into account. This is also important for balance, allowing people to realise themselves personally here.”

Mutual respect, listening to each other, sharing responsibilities, and self-realisation are the main values of working in a Federation. Turns out that a key aspect of sustainable community building is actually spending time together and nurturing human relationships. However working without financial frameworks and depending on incomes based on consumption can lead to burnout. Working in collectives requires a massive amount of creative energy, and oftentimes the budget cannot finance all artists involved in realising a project. I had to learn this the hard way: leading a group of people who work with you out of passion is one of the least forgiving tasks I have ever done in my life. I was entirely grateful for the efforts of my team members, but in lack of financial compensation, people needed to focus their energy on jobs that can sustain them. This problem is so pressuring that it affects smaller groups just as big initiatives. As we mostly depend on our audience, balancing between bankruptcy and becoming “sell-out” keeps us in constant worry and constraint.

“VV: It’s also important to note that you are completely independent financially. That means you don’t receive any regular support that could potentially influence your cultural content.

SK: This is true in the sense that there is no grant money locally today, and we are not dependent on anyone culturally. However, I hope that if we talk here again in a year’s time, this will change, because our goal is to alleviate the financial burden on the events we host. The fact that revenue is also a consideration may actually imply a kind of dependence, as it somewhat limits the range of events we can host.

VV: Why do you think Gólya could keep up in this framework against for-profit venues?

SK: I think it’s because we operate based on a mission and try to apply this in our daily activities. It’s important that these values are recognisable and all about cooperation, and I think places that can embody these values tend to be successful. There are other places that try to claim similar values, but eventually, it often becomes clear, even to those not very familiar with Budapest’s nightlife, that something is off. A phenomenon is emerging, which I might describe as an ‘underground industry’ because it’s becoming fashionable to be outside mainstream culture. People sometimes see Gólya in this way, too, but the differences usually become apparent when these critics spend a night in a for-profit venue.

VV: I really like the term ‘underground industry.’ I’ve described it as ‘underground is the new pop,’ since the practices and symbols of counterculture have started to gentrify into something that fundamentally has nothing to do with grassroots initiatives.

SK: Yes, but still, if someone thinks a bit deeper—and I think young people typically do think more deeply—they care about what happens to the money they spend on a beer. It is clear that, in our case, money supports our transparent mission and helps sustain this place. Evidently, personal enrichment, dividends, or vacations in Thailand won’t come out of this project. In downtown venues, where undeniably great music programs exist, it’s often visible that the revenues don’t necessarily go back into the system or dimension with which the performers could even identify. On the other hand, you can’t place the moral burden on the organisers and musicians because there are very few venues in Budapest, and Gólya can only host such events three days a week.“

I could not quite put my finger on the genesis of the ‘underground industry’ in Hungary, but in the past three years the misuse and abuse of free culture was prevalent. Just to name a few examples, freetek parties were organised that cost 4500 HUF (around 12 euros – note ed), intentionally made ruin pubs opened at Népszinház Street charging 1100 HUF (around 3 euros – note ed) for Kőbányai beer, rural cooling towers served as huge displays for Coca-Cola and Maybelline advertisements, or the americanisation of Strilich Pál Scout Park for a festival that does not pay their local artists.

It is needless to stress how problematic the commercialisation of such subcultures and places is. The previously mentioned tool for cultural freedom is taken away from minorities, and former safe places are flooded with middle-class club dwellers who do not even bother to be educated about the music they are listening to or the culture they are devouring.

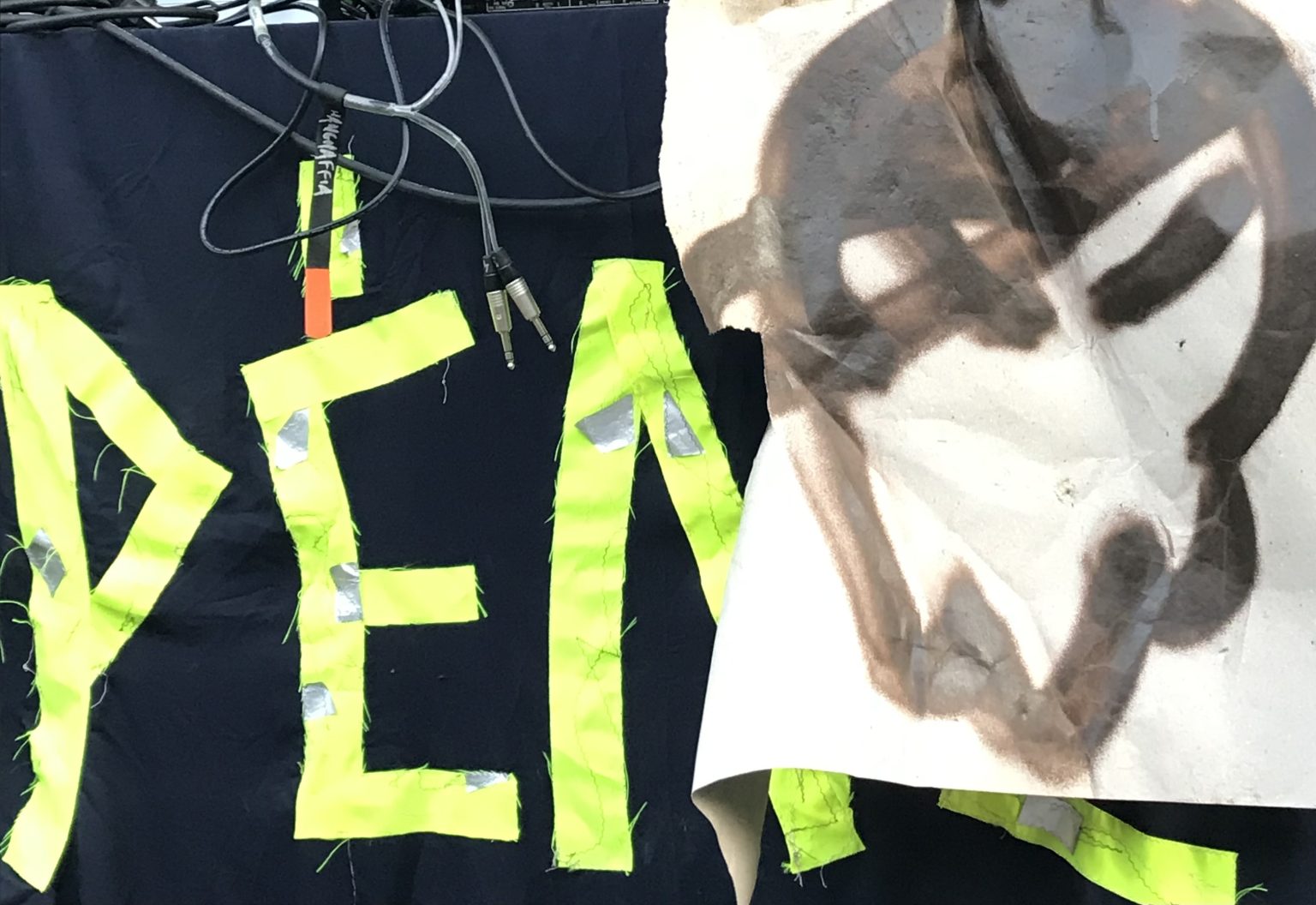

PÉNZ banner during a free rave festival at Bazsi

“VV: The question of safe space. Which ones are the most prevalent safe venues in Budapest?

CSG: The small number of accessible venues for organisers in our community has been a serious issue ever since I’ve got insight into this topic. However, I must pay respect to the accepting venues and cultural spaces that showed interest and provided a helpful environment to us, such as Art Quarter Budapest or our beloved lounge and bar Susuka. As mentioned above, the governmental pressure of intolerance towards social and ethnic minorities makes it even harder to find venues that clearly represent acceptance, so the open gestures of these places are highly appreciated by Marmint and its artists.

VV: How do you think today’s political climate affects the alternative music community?

CSG: There is a seriously negative impact on our community by the various acts of the government’s hate propaganda that have been rapidly emerging in the previous years. One of the most relevant problems is the backlash against ethnic minorities and the queer community. Since many people among the artists and audience of the scene have to face this extrusion daily, it’s highly important to focus on creating a safe intellectual circle that welcomes people of diversity. Gladly, the labels and venues Marmint has worked with so far have proven that this establishment of a safe zone can be made possible.

VV: What do you think a scene needs for alternative music to flourish?

CSG: Autonomy and the mindset of its necessity to keep providing confidence to the newcomer artists. In the first place, artists should be given a chance to represent themselves the way they want to be seen, that’s essential for one’s self-reflective abilities to start developing.”

111 records was established with the same intentions and values. We wanted to create a platform that could support emerging artists and give them a sense of community where they can be themselves and feel understood. After three years of working together in Family Fast, humour and the internet culture become our main weapon against the pressuring mainstream waves. After the 2020 lockdown, we got so good at not meeting in real life that part of us was terminally uploaded to servers and online forums. Musical forums and netlabels have been present since the 1990s, music and file sharing are nothing new, but something has changed after we broke free from self-isolation. Many talents from Gen Z, who grew up as internet kids, discovered multi-media self-expression and started sharing their works on social media sites and music streaming services. SYNC VA came out on 111records on January 11th of 2023, featuring twelve incredible musicians. Diversity is a key element in the album, which we willingly aimed for in the name of pushing boundaries. Mármint Agency shared the first exclusive mix on their Soundcloud three months later, and since then, they have been consistently active and augmenting. Another often occurring topic between SUTA and me is consistency, which I think is a very clever take of his, and he acts up on it and utilises it to keep the platform running.

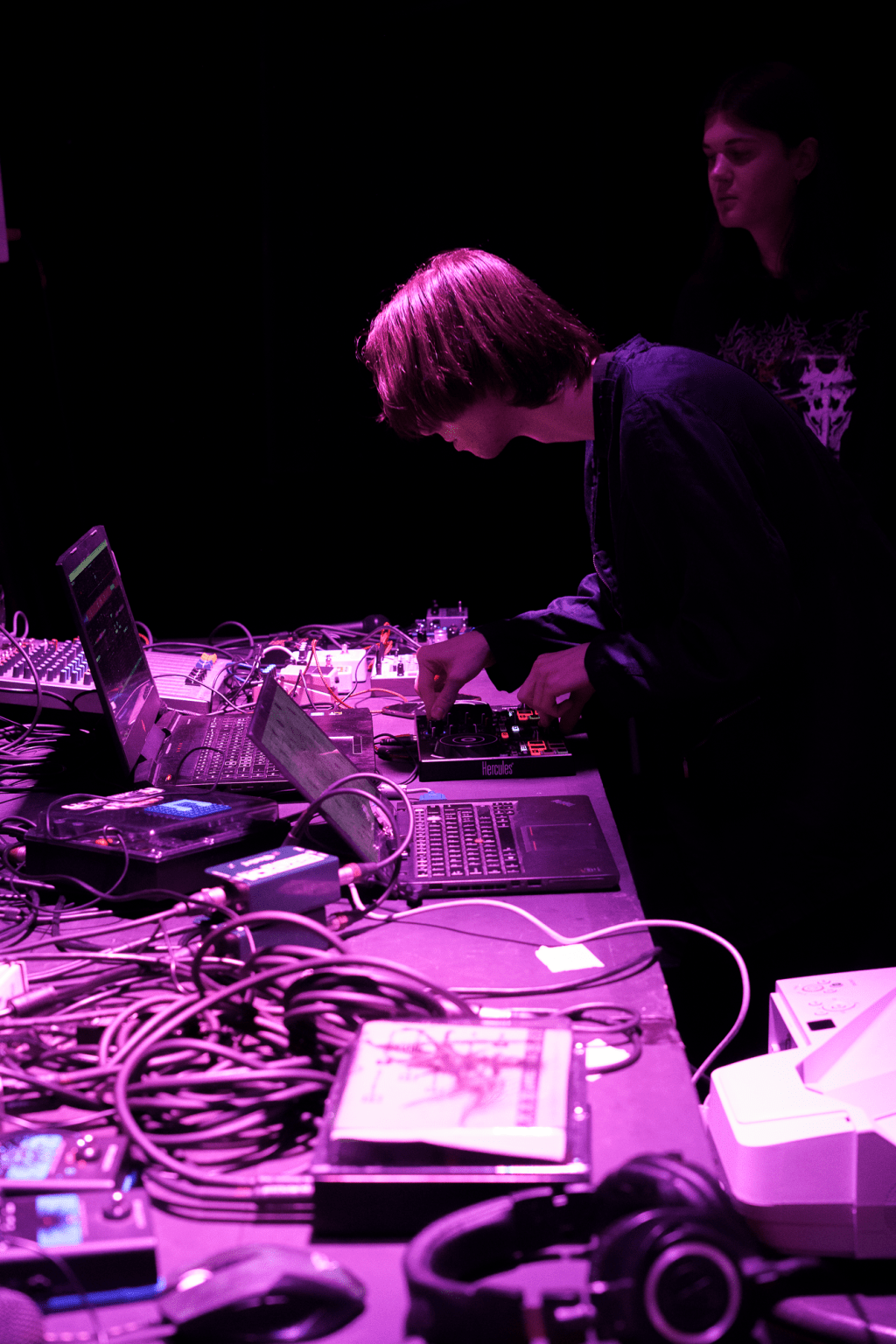

SUTA and asvanyviz2 during SCENE 111records showcase

“VV: What is the mission of Marmint?

CSG: Marmint does not try to serve as a platform with a certain envisionment in sound or a visual representation sense. There is no agenda or aesthetic that the featured artists on the platform should stick to because quality control could hold back their autonomous process. The most important part is to give these artists a chance for the first time to represent themselves the way they would feel comfortable.

VV: What is an Agency anyway? Why do you think the existence of agencies is important in alternative scenes?

CSG: To be perfectly honest, the only reason that Marmint became an agency was its impersonation as a talent agent for Hungarian experimental electronic musicians. You could say it’s an unorthodox way to reach out to artists. It might ease the pressure for the artists and let them consider their work not as much as a contribution but as a self-sufficient piece that can still fit in this wide sense of the platform.

VV: What do you think about the emerging platforms of the Budapest scene?

CSG: I could sense a rapid growth of interest for younger artists and listeners in the local experimental music community ever since Covid-19 ended. Labels like 111records, Zaj+ allow Gen Z and younger artists a chance to publish their works or daddypowerrecords that have been consistently supporting up-and-coming musicians since 2017. However, in a scene like this, there is always a feeling of lacking exposure for musicians. I would rather consider it as a problem that comes from the amount of listeners and people that can be reached by the already existing platforms. We live in such a small country where the number of people interested in this kind of art is pretty limited. If I could think about a solution, it would definitely be about involving countryside micro-scenes and finding isolated artists who still remain unknown to the Budapest scene.”

Marmint Agency’s efforts to decentralise and include the countryside in the cultural conversation are crucial steps toward a more inclusive and diverse artistic landscape. Moreover, the above-mentioned formulation of the ‘Hungarian sound’ couldn’t even be imagined without it. By nurturing local scenes and supporting emerging talents, they challenge the notion that meaningful art can only thrive in urban centres. This decentralised approach is not just about geographical expansion but also about fostering a broader, more connected community.

The alternative music scene in Hungary serves as a microcosm of the broader cultural battle faced by many around the world. It reminds us that true cultural freedom requires ongoing effort, mutual support, and a willingness to innovate and adapt. I encourage all artists to stay brave and adventurous and to share their message with the world by overcoming their personal programs and to become an active member of their community. Despite the challenges posed by limited funding, venue scarcity, and political tensions, the passion and creativity of emerging artists shine through.

These stories about grassroots organisation, democratic values, and the fight against commercialisation highlight a path forward for alternative cultures. The journey is far from over, but with the dedication of individuals and collectives who believe in the power of art to transform and unite, there is hope for a vibrant and sustainable future for Hungary’s alternative scene.

This article is brought to you by easterndaze as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.