EM GUIDE: Ellen Arkbro “I love making sound in a room and having people there to experience it”

Ellen Arkbro in New York (Photo: Victoria Loeb)

Let me start by saying how much I’m looking forward to your CTM performance on February 1.

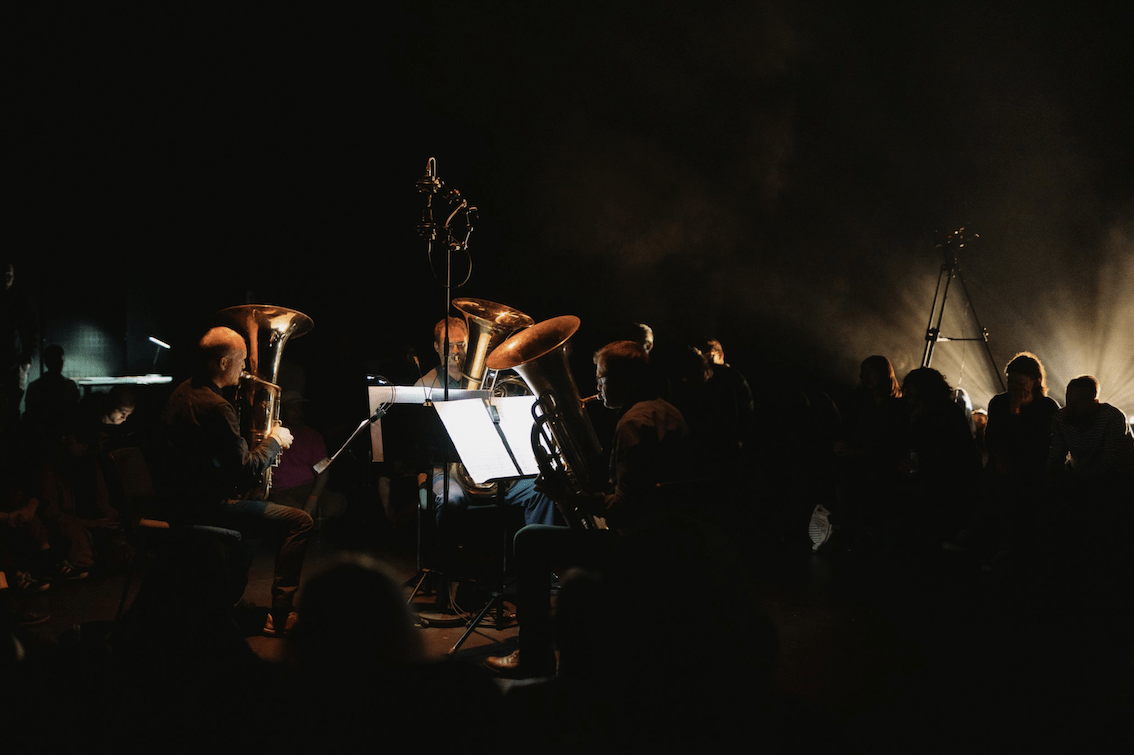

Ellen Arkbro: I hope it will be a good one. It’s a tricky piece to perform, the tuba trio, but they are excellent players, so it should be fine.

What’s the tricky part of it?

Ellen Arkbro: First of all, playing sustained tones on the tuba requires a lot of air, and to do that for 25 minutes straight is challenging. Then there’s the tuning aspect—they have to make a lot of small adjustments to get the tuning right, most importantly they need to find a way to hear each other well in a new space. I’d say the piece doesn’t really work unless the chords are really in tune, it kind of falls apart because it’s so simple and basic. It’s only when the three instruments come together as one sound that it really becomes something, you know?

Is that you as the musician thinking about how it sounds? Or do you think about how the audience might experience it as well? I ask because, often, musicians feel like, “Oh, it’s not working at all,” but do the people listening really hear or see that?

Ellen Arkbro: I mean, this is obviously my experience and it’s related to my intentions with the music I’ve written. So I guess someone else could experience it very differently. But, yeah, it’s a tricky question, and it’s sort of impossible to answer. I do have a feeling that when you work with material that’s so bare and stripped down and simple, it’s necessary to do it with precision.

Ellen Arkbro (Photo: Kali Malone)

I really like the title “Clouds for Three Tubas and Chords for Trumpet”—it feels poetic. Does the music itself inspire a more poetic title for you?

Ellen Arkbro: In a way, yes. Though the title is still kind of dry, I’d say. Somehow the music slowly evolves through harmony in a way that feel like the movement of clouds. When you watch the sky and see clouds slowly passing by, creating new landscapes—the music feels a bit like that I guess. And there’s something moody about the music too, a bit bluesy, a certain melancholy.

Clouds can symbolize so many things. They could be dark before a storm, or just a single, perfect cloud against a clear blue sky. So it opens up the imagination, especially when you hear the music—what’s the intention behind it?

Ellen Arkbro: Exactly. What I like about the clouds reference is you can study clouds and imagine so many different things. You can see all these different shapes and formations happening. That’s sort of how I think about this music too: it’s so simple that the only way it becomes interesting is when you start to add your own imagination to it…

It’s like a material that can be shaped by the minds of the listeners. Is it harder to perform in Berlin when so many colleagues will be present?

Ellen Arkbro: My nervousness has less to do with the city—whether it’s Berlin or a tiny town in Sweden—and more to do with the size of the space. I find that I tend to be more nervous in smaller spaces, because you’re closer to the listeners and you’re interacting before and after the concert. And I find that the most nerve-wracking place to play is KM28 in Berlin, because that’s the combination of a small space and all of your friends. And everyone’s sort of expert listeners.

I’ve heard people say that playing in big stadiums can in some ways be easier because the audience becomes an abstract mass. Imagine being in front of 70,000 people in a stadium.

Ellen Arkbro: Maybe yes, the people in the audience become so abstract somehow. That’s tricky in a different way. I’ve played a lot of organ concerts in churches when you are far away on a balcony, sometimes with your back to the audience. There’s some kind of buffer that allows you to stay in your own world that I most often find helpful for the focus, especially when you are playing very slow music that you don’t want to rush.

But what was I going to say? Oh, right—something that makes me nervous is whenever I sense that there are expectations that won’t be met. Like if people expect me to do a certain thing, or if I feel my music is in the wrong context.

Sky in Nepal

As you just used the word “expectations,” listening to your releases so far, you’re definitely not a one-trick pony. While others might stick to one sound paradigm, you keep exploring new horizons. Why is that? Do you get bored quickly? Are you extremely curious? Do you prefer a more ambitious path?

Ellen Arkbro: Some of the artists I admire the most are really complex and do a lot of different things and are sort of impossible to pin down. That’s always intrigued me. Because that’s life and people! Before doing the song record, “I Get Along Without You Very Well”, I somehow felt a bit stuck creatively. I felt that the work I was doing was moving in one direction and I somehow couldn’t see in front of me, how it would move forward. So I felt that I needed to do something very different to get stimulated and I went back to where my inspiration to making music started, to something I had done earlier in life: writing songs. And it turned into a beautiful thing involving a lot of the musicians that I played with when I was younger. It was sort of a return to my early musical curiosities.

Did it also have to do with bringing in the voice? The voice is so significant, and some people really need a vocal element to connect with music. Was that part of it?

Ellen Arkbro: Honestly, I find it difficult to listen to my own voice. I do like the experience of singing and I do like to write songs, but in a way, I wish all my music was instrumental. I sometimes regret that I made a song album because it sits in a place where the aesthetics are a bit unclear to me.

Does it have to do with the sound of your voice, or is it also that bringing in words obviously changes the narrative?

Ellen Arkbro: Yes. It’s not really the voice—it’s the words and that I am actually expressing something in words that I have a problem with. If I was singing in a language that no one understood, including myself, it would feel different.

That connects to performing live. As a musician, it can be tough to be shy, because everything goes back to performing to earn money when artifacts aren’t selling well anymore. Do you sometimes wish you didn’t have to be on stage?

Ellen Arkbro: I honestly love presenting my music live, but I don’t necessarily love being on stage in the theatrical sense. I love making sound in a room and having people there to experience it. That, to me, is so much better than putting out music on a record. I would do that every day if I could. And when I perform, I’m not putting on a show. It’s more like, “We’re in this space together; here are the sounds I want to play for you—let’s experience them together.”

That can be challenging, because some audience members pay entrance and expect a certain kind of presentation, right?

Ellen Arkbro: Yes, but ideally you’d have a space where you’re always working and people can come and experience the sound when it’s ready. Like La Monte Young’s “Dream House” or other continuous installations, or how Catherine Christer Hennix performed at Moderna Museet in Stockholm in the 1970s with her ensemble—to have the instruments set up, the musicians there, and say, “Okay, now it sounds right. Let’s invite an audience.” That would be a dream.

I remember going to the Dream House in New York and spending hours there without needing to know exactly where the sound came from. At a concert, it’s trickier. Venues aren’t always set up to transport that feeling. You walk into some spaces and you’re already looking forward to the music more than the place.

Ellen Arkbro: Right, and I often work with sounds that need to blend together with the space in a specific way. It has to be adapted to the space and mixed in a way that you can only mix if you really know the room, but I am getting better at it. But traveling someplace new and only getting a two-hour soundcheck can be difficult.

Microtub performing “Clouds for three tubas”

So what does a sound need to get your attention?

Ellen Arkbro: It has to be cute. (Laughs) No, but really, I think there’s a certain kind of complexity that I am drawn to—and I need to find it beautiful, of course. I can be transparent with my intentions of creating beautiful music, not everyone is interested in beauty but I look for sounds that I find beautiful and usually that’s a sound that is a bit complex, yet simple, and maybe a bit hard to define. I love to be a bit perplexed by the sound, I love when you don’t quite understand what’s happening. That childlike sense of wonder is important to me.

So it could also be about hearing something new, even if it’s new only to you personally.

Ellen Arkbro: Yes, exactly. Though newness in itself isn’t necessarily interesting, I do love encountering something I haven’t heard before. It can also be something that stays long enough so that I try to grasp it (and fail)—sustained sounds are more interesting in that way to me, rather than short ones that so immediately disappear.

Sky in Bologna

Do you remember the first sound that struck you so hard you couldn’t forget it?

Ellen Arkbro: One thing that comes to mind as a really influential sound experience that I often mention is Marcus Pal’s sound installation “Welcome in, outside” in Stockholm ten years ago. It was a sine wave chord played on a very loud volume, and the specific frequency relationships, how they were played from different speakers in the room, the frequency band it was in triggered a harmonic distortion in the inner ear that was so intense and had endless chordal variations that shifted as you moved through the space or titled your head slightly. You could compose your own chordal progressions as you were dancing through the space slowly. It was one of the strongest, if not the strongest, experience of as sound that I’ve had. You could only be in there for ten minutes or so without risking damaging your ears because of the loud volume, but it was an incredible ten minutes.

It’s also a reminder that, as we age, our ability to hear certain frequencies disappears. It’s frustrating to realize things you heard before might be gone now.

Ellen Arkbro: Definitely. We all experience the world differently always of course, but with something like the hearing and how you can measure your hearing range it becomes so clear. Someone can say: Do you hear this? And you don’t hear anything. My grandmother, and my dad, both got hearing aid early on, so I’m expecting that it will happen to me too…

But I’m hopeful technology can help.

So loud music can still be beautiful to you?

Ellen Arkbro: Absolutely. Loud or quiet doesn’t matter. Although most of the music I write is in that mezzoforte range. What I find beautiful has more to do with the overall experience—if it’s perplexing in a way that triggers that feeling of wonder, that’s beauty to me.

Sea in Pantelleria

I read that you work in precision-tuned harmony, specifically just intonation and meantone temperament. Can you explain that to someone who hasn’t studied music?

Ellen Arkbro: Basically, meantone temperament and just intonation are two different tuning systems–ways of tuning instruments or intonating on an instrument. Meantone temperament is a historical tuning where you favor the in-tune thirds (narrower than on a piano today) and so you narrow the fifths slightly to give rise to pure thirds. Just Intonation is a tuning system based on the harmonic series where all the intervals are rational (whole number) relations.

How do I have to imagine what it means to “use a traditional renaissance tuning in a non-traditional way”?

Ellen Arkbro: That’s referring to “for organ and brass”, a piece that I wrote for meantone tuned organ and brasstrio. I was using the meantone tuning in a way that was originally not intended, modulating between the different septimal sounding intervals.

The whole piece was composed with only a set of intervals that has that very bluesy sound, they sound low and a bit heavy. The intervals are beating a little bit, so they’re not completely in-tune, they’re a bit lighter and has a more confusing pull than an in-tune septimal interval in just intonation, but they still have that 7-quality, although slightly different. It’s the same kind of intervals that you can hear in La Monte Young’s “The Well-Tuned Piano,” and I was inspired by that piece and the movements between different septimal intervals when I wrote “for organ and brass”

Tubas warming up

I bring this up because I’m particularly interested in how you choose the instruments you mostly work with—pipe organs, renaissance organs, trombone, microtonal tuba—and the tuning. Is there a relationship between the process of choosing these instruments in the first place and all that’s behind them, or is it more like you discover it afterward?

Ellen Arkbro: I’m drawn to the sound of air flowing. Because I write very slow music that can feel somewhat static, that air adds a liveliness to the chords that could otherwise feel a bit dead. So I love wind instruments and I’m interested in the textures that you get when you work with precisely tuned harmony in the lower register so I’m really drawn to low instruments like tuba, contrabass, trombone, cello and bassoon…

Another important aspect is tunability. I work in just intonation, so an instrument with a fixed tuning doesn’t interest me as much. For different reasons, I almost never work with piano—I don’t love the sound first of all, and retuning a piano is a hassle. With brass instruments, they have a natural harmonic series and it comes natural with the instrument. Like with singing: choirs tend to naturally tune the thirds lower (like in the harmonic series), that’s how you blend together.

When you say you are a slow worker, does that also have to do with trying out certain ideas on different instruments and in different tunings, or is it more that you let the ideas rest?

Ellen Arkbro: A lot of letting things rest. Partly, I’m slow because I spend a lot of time not working during the process (laughs). It sometimes take some time to understand what’s interesting about an idea. Or I might have an idea, but I’m not 100% certain that it needs to exist in the world, or how it should exist in the world. It can take time to get it right. With the tuba trio it’s taken some years to play it, record it and understand it…

But when you say you don’t work, you rather mean you let the idea work within you, to see if it still resonates with you?

Ellen Arkbro: Yes, because ultimately it needs to align with your inner compass since that’s the only guide you have. So it can take some time to catch up with yourself…

In your working process, how do you see the combination of electronics—like SuperCollider—and an old church organ? Do you see it as a kind of time travel, or do you just treat them as different ways of generating raw sound?

Ellen Arkbro: It’s not time travel for me, the thing that connects these different instruments is the closeness to the raw building blocks. Blowing air through an organ pipe or generating a saw tooth wave, working with chords. It’s only different ways of generating that raw stable sound. When I work in SuperCollider I rarely use anything other than the very raw oscillators, maybe some filters, but never reverb. Sometimes the translation from something synthetic to something acoustic can be frustrating, I’d hear something perfectly in tune in my computer and it would have a clarity that’d get lost when you try to play the same thing on acoustic instruments. I still struggle with that sometimes.

I’m always fascinated by SuperCollider. It seems so abstract, like you have to know exactly what to write in code, but then, as soon as you hear the sound, it might be different from what you initially imagined.

Ellen Arkbro: Yes, it often is. It’s frustrating sometimes because you can have conceptual ideas and formulate them in text, but when you press play, you’re back in the domain of sound, which can diverge from the concept. It’s easy to get stuck in ideas about numbers and synthesis techniques, but you have to listen and be guided by the experience of the sound. But more so, I find that programming can be very stimulating, if you are curious and stay open to unexpected results. Like anything else, it’s an instrument that you have to learn how to play. I have lost touch with it somewhat recently and want to find a way back to the fluency.

Is it also a relief to switch fields? Like, if you get stuck working on something acoustically, you might jump over to electronics, and it clears your head?

Ellen Arkbro: That’s somewhat part of it. I wouldn’t want to stay with one tool or one instrument. Switching perspectives brings me back to the center of my practice, which is exploring harmony, and blending of space and harmony, and of mind and sound. And I need for all of my music to feel necessary somehow. I wouldn’t want to put anything out into the world that didn’t feel like it had to be out in the world, whether that’s because it’s meaningful to me, or because the music doesn’t yet exist, or because it brings an interesting perspective on something.

Performance of “For Organ And Brass”

Does that strict sense of necessity ever change afterward? Like, do you think, “I’ll delete that release from Discogs because it wasn’t necessary”?

Ellen Arkbro: Yes, it always changes and it keeps changing. I’m fighting that impulse. If I could, I’d probably go and delete some old releases off of Discogs, and I have tried to once but then there are people on there who keep track of everything— “Why did you remove that? It says printed on the record that this artist is playing on this release. You can’t change history.”

I guess I’m somewhat careful about what I put out, but it’s a balance, I don’t want to become someone who never releases anything. I’m a Virgo and so I like to be in control, but I also accept that I can’t be, and in the end it’s more beautiful that things slip out of my control. That’s what it is to be human.

That’s also why you released your debut album somewhat “late,” at 27?

Ellen Arkbro: Yeah, I guess 27 could be considered late. Honestly, I hadn’t thought much about releasing music before that first album, and I wasn’t even planning to release that music on record. My mind was elsewhere. We did a concert performing ‘for organ and brass’ in Stockholm in 2014, and somehow a recording from the concert circulated. It ended up with James Ginzburg, who runs Subtext, who wrote me and said, “Let’s make a record.”

It’s interesting, because you started so early playing in bands, then studied music at 20, so it sounds like music was always present. One might imagine you’d be keen to release something sooner.

Ellen Arkbro: With my first band, that I started when I was 11, I definitely thought we’d make an album, or many albums. We played together until we were about 15, and I thought that that band was going to be my life—that we would tour the world. But that obviously didn’t happen.

Organ in Strasbourg

Are the others from that band still doing music?

Ellen Arkbro: No. For everyone but me, I think it was more of a fun way of hanging out together. But I was stupidly serious.

So you’re ambitious?

Ellen Arkbro: I guess so… I definitely have a lot of things I am dreaming of realising, and some things that are a bit bigger projects… but when things start to matter a lot to you, you also get scared to fail. So I’ve kept many of these bigger ideas in a dream phase for a while. But yes, I guess I’m ambitious. Otherwise, why do anything?

Maybe just for beauty?

Ellen Arkbro: I mean, yes… I’m interested in the sounds and in realizing my sonic ideas. But I don’t necessarily need to earn a living solely from making music. I could imagine doing something else to pay my bills if that gave me more of a freedom to explore what I want.

Anyway, back to the imagination of sound. Is it easier to reach what you imagine when you produce electronically, or when you compose for an instrument? Or do your ideas often evolve once you start working with real players?

Ellen Arkbro: It usually evolves, it has to. There’s never a perfect one-to-one relationship between the idea in my head and the final piece. The idea is more of a starting point, and then you meet with reality—whether it’s the intense rawness of synthesis or the instability of acoustic instruments. I try not to let the concept override what I’m actually hearing, but sometimes you get so attached to an idea that it’s hard to let go. Ideally, I work directly with the instruments or the ensemble that I am composing for. Working with synthetic sound when you are composing for acoustic instruments can be misleading, especially when it’s about tuning, that naturally is fluctuating on an acoustic instrument and tuning together is difficult.

Organ in Athens

The other thing I wanted to come back to briefly are the places we perform— like for your own music you work with church organs and perform in churches. These days, we often find ourselves in churches, in places we used to avoid earlier in our lives, right? But now look at us—we’re in academia, in institutions, in churches. Do you think about that often? And what’s your feeling about it?

Ellen Arkbro: I do think about it. I mean, I grew up in churches and also grew up singing in choirs who’d often perform in churches. I spent a lot of time in those spaces and feel comfortable in them, at home. But ultimately, what I’m interested in is the instruments, the sound, the acoustics, the resonance, and the spaciousness. Sometimes, like when playing in Italy, it’s more pronounced that you’re in a church space — and just to get access to the organ you have to meet with the priest and explain your intentions. Whereas playing in a church in Holland can feel like playing in a bar; it’s been transformed into a different kind of space.

It also changes how we experience things. Walking into a church usually feels cold, more formal. I might feel I have to be more silent, so my behavior changes. Does that ring true?

Ellen Arkbro: Yes, the silence part is interesting. I have mixed feelings about it. In one sense, I appreciate that kind of attention and presence, if I imagine that it’s directed to the music and the experience. But I also don’t want anyone to feel that they have to disappear or for anyone to feel uncomfortable. If the church context helps to create a meditative experience focused on the sound, then it’s a good thing; if it distracts from it, it’s not.

It fits into old categories—here in Germany, there’s still a distinction between so-called “seriöse Musik” (serious music) and “Unterhaltungsmusik” (entertainment music). Playing in a church sometimes brings this serious or even pretentious tone. For me, it can make it harder to slip into a purely emotional experience. In the La Monte Young space, the “Dream House”, you can lose your sense of time, even fall asleep if you like. But in a church, you might feel anxious about making noise if you did that. So it becomes more intellectual, more formal. Do you see what I mean?

Ellen Arkbro: Yes, I understand. I’m serious about the music, and I hope listeners are serious about wanting to experience it but ultimately, what I’m after is a contemplative experience. Different spaces will work for different people, but ideally you want as few distractions as possible and a chance to just be with the sound.

Performance in Leuven

I interviewed Heiner Goebbels twice. He once said he was terrified of teaching at a university, worrying the students would see he had no real knowledge, that he was just faking it. It’s amusing, but we all know that feeling of being an imposter. I came across a quote from you that suggested you sometimes feel the same, like you still wonder if you know anything at all.

Ellen Arkbro: Definitely. I feel it every day, and it can be hard to work while thinking, “I don’t know anything.” But then I start working and realize that I have preferences and ways of listening that can guide me. I do know something, at least something about making my own music. Unless it becomes incapacitating, I think that the feeling can be a good thing. It means that I’m always at the beginning of something, which is a place I love to be.

Right—more knowledge reveals a bigger field of unknowns. Total certainty probably doesn’t exist; in fact, you need a certain level of knowledge and experience to follow your intuition confidently. When you start out, you might just run in circles, but eventually you trust yourself to explore. Do you agree?

Ellen Arkbro: I do. I also feel knowledge is fluid, and it can fade if I’m not actively working every day. Then it returns when I re-engage with the work.

It’s like writing—when you’re out of practice, you think you can’t do it, and then, once you dive back in, it comes together again.

Ellen with Catherine Christer Hennix in New York (Photo: Marcus Pal)

Speaking of ambitions, you’ve often referenced other artists—Arthur Russell, La Monte Young, Catherine Christer Hennix—as role models. Do you feel you’ve positioned yourself within their coordinate system, so to speak? Are you on that same map now, or do you still feel you’re just starting out?

Ellen Arkbro: I do feel very connected to their work. I worked with Catherine Christer Hennix before she passed away. I play trumpet in the Kamigaku ensemble. We’re doing a memorial concert for her in Stockholm on Sunday (January 26). And I studied with La Monte Young in New York. They both devoted their lives to their work and their ideas and that’s something that’s deeply inspiring to me. And the things I want to explore are very much connected to the things that they were exploring. But it’s a difficult question to answer. We also live in a different world now. So much has changed since the 60s and 70s. I do have a lot of things that I want to explore and so in that sense I feel more like I am only in the very beginning.

Or magazine’s subtitle is “Insolvenz und Pop”– “insolvency and pop.” It started ten years ago from an interest in artists’ upbringings—family structures, larger communities, and economic realities. You once mentioned you could see yourself doing something else for money, but here you are. Do you question your path? Or is it a given, and you just struggle along like everyone?

Ellen Arkbro: I never really made a choice. I always knew I was going to be a musician. I couldn’t imagine another life. Now that I’m older, I can imagine other lives.

Did your parents encourage you toward an artistic life, or did they worry and suggest a backup plan, like many parents do?

Ellen Arkbro: They never really steered me in any direction. Neither of them are artists or musicians; my dad is a nurse. But they always encouraged me to play music and they came to every concert I played. I think they could see early on that this was where I came to life. When I got into more experimental music and my music got “weirder”, I guess they both got a bit nervous, they couldn’t imagine that there would be a future in making this kind of music. My dad’s a very curious music listener and introduced me to a lot of music when I was younger. He’s always been open-minded and comes to my concerts and is very much engaged in everything that I do and wants to understand it. My mom stopped coming to my concerts about 10 years ago, after I started making this slow music with sustained chords. In a way I wish we could talk more openly about it but she still calls me before every concert I play in Stockholm and says: “I am sorry, but I can’t make it!”

I read that, at some point, you had moved 24 times in 31 years. Why would anyone move so often? Did your family already move around a lot?

Ellen Arkbro: It’s more now! I don’t know. I moved around a bit as a kid but I especially moved a lot in my early twenties, mostly because it was so difficult to find housing in Stockholm so I’d stay three months here, six months there… Anyway, I have lost count these days. And I travel so much, and do longer artists residencies so I don’t know what’s what. Sometimes it feels like I live nowhere and everywhere, which can be exhausting, but it also forces me to be extremely present wherever I am.

I notice the wall behind you is totally white, while mine is covered with stuff—I’ve been in the same flat for 15 years. As much as I love my extended travels I love returning to my base. It sounds like you’re constantly on the go. Do you see yourself settling somewhere eventually?

Ellen Arkbro: I’d love for that to happen someday soon. I’m getting better at always traveling, but it’s tiring. I’m dreaming of having a place that I can keep returning to, but I don’t where yet.

Ellen, thank you so much for talking with me at length. I’m really looking forward to seeing you play in Berlin.

This article is brought to you by Kaput Mag as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.