Adam Harper – Can AI vocals serve people?

I’m not referring to the degree of its potential impact (though it certainly is set to have a huge impact), I mean that for people using it and witnessing the results alike, AI comes inextricably tangled up in wider contexts and trends: capitalism, the power and ambition of Silicon Valley, disinformation, crimes of fraud and copyright infringement, high levels of water and electricity usage that connect it to climate crisis, and even the aesthetics of surging neo-fascism. And like many technologies before it in modern era, AI has been understood in opposition to fiercely fought notions of art, craft, value, humanism and fears of professional or spiritual “replacement” that go back hundreds of years. This was also true of sound recordings themselves, which some in the early twentieth-century thought represented the dehumanization and death of music. But times change, and today many music lovers see vinyl as among the most authentic and respectable forms of listening.

Music technologies don’t just produce signifiers (such as musical performances and their constituent elements of sounds, notes, timbres, rhythms), they are themselves signifiers. What changes with the times is what is signified and how the signifier is judged, and as time passes old technologies come to seem less like threats and more like classics. This is true even of those technologies that are the most close to home because they manipulate voices and thus are most viscerally tangled up in agency, identity and the complexities of the body, such as the vocoder, the Sonovox, AutoTune, Vocaloids, or something we’re now so used to we hardly think of it: the human voice reproduced on the phonograph or telephone. But with AI having just lurched over the horizon with its frightening allies in tow, how useful is it to think of it as just another in a long line of musical technologies that have come to be accepted as part of music’s toolkit? Put another way, we survived the vocoder, didn’t we?

“Technologies that are (…) tangled up in agency, identity and the complexities of the body”

Not all of us. The vocoder is a device that breaks down a voice into a series of signals at certain frequencies, capturing its vowel sounds and percussive rhythm independently of the voice’s pitch. Those signals can then be imposed on another sound source—most famously a synthesizer—allowing it to talk or sing. The device goes back to the 1930s, but it was later made famous in music by Sly and the Family Stone (“Sex Machine” on Stand!) and, repeatedly, by Kraftwerk. But the vocoder wasn’t just used for music. As a key component of the SIGSALY communications system, which encoded voice for allied communications in the final years of World War 2, it was involved in the bombing of Japanese cities such as Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Dave Tompkins, in his book on the vocoder How To Wreck a Nice Beach, claims that an anonymous Signal Corps officer later recalled the vocoder intoning the words “hell bomb”.

This is a unique entanglement for a musical instrument to have—violins, guitars and pianos haven’t been involved in mass destruction. To be sure, it’s probably not an association most listeners to vocoders are aware of. Nevertheless, the eerie, metaphorically “dehumanized” sound of the vocoder offers a perspective on and is aesthetically inseparable from twentieth-century technoculture writ large—the rise of mediating systems that seem to collapse both distance and responsibility—and as such beguilingly represents impersonal forces of authority and control in Laurie Anderson’s ‘O Superman’ and the music of Kraftwerk and Afrika Bambaataa. The implication of the vocoder in military operations doesn’t necessarily make it inappropriate for art, but it can mean there’s a darker element in listening to it that can be mobilized for a critical examination of the modern world and its potential futures.

“the voice of tech-capitalism, anti-humanism, climate destruction”

In this way, the voice of AI can also be heard as not just the voice of a machine but the voice of tech-capitalism, anti-humanism, climate destruction—even the voices of those who have no understanding of or respect for creativity as a rich social encounter, their rise to power and their desire to build a God. This is a possible hearing of AI whether artists and their listeners understand it critically, self-consciously or conceptually (as Holly Herndon, Grimes and Jennifer Walshe have) or not (as in the AI “slop” filling up Spotify and other platforms). Put crudely, some music involving AI is “about” AI, and as such can involve a degree of critical distance, while some music, for better or worse, is simply AI.

But there are some key distinctions between the vocoder and AI voices. Firstly, even if it radically modulates the sound of a voice, the vocoder captures and correlates with a real-time vocal performance, whether that performance is live or once live and now being reproduced by a recording. The Sonovox (later called the Talkbox, used by Roger Troutman in the band Zapp) and Autotune are similar to the vocoder in this respect. As “dehumanizing” as we might interpret these devices to be, they do relate directly to the actions of a human body. AI, on the other hand, generates a new performance based on its extensive training in the vocal performances of others.

Secondly, it’s easy to tell when you’re hearing a vocoder—or, at least, that you’re hearing something weirder than a ‘natural’ human voice—but that’s not necessarily the case with AI or even some of the more sophisticated instances of vocal synthesis, such as Siri, Alexa and the like. Autotune is good comparison here, because there are two kinds of Autotune: the kind you don’t typically notice, because it is subtly correcting the pitch of singers, and the kind you notice, because its settings have been turned up so high that the voice now jumps from one note to another step-wise, a striking technique made famous in the West by T-Pain and similar artists, but also used around the world. The noticeable kind is appealing not because it’s ‘human’ in the narrow, conservative sense of the term and its aesthetic implications – Autotune music is of course a ‘human’ music.

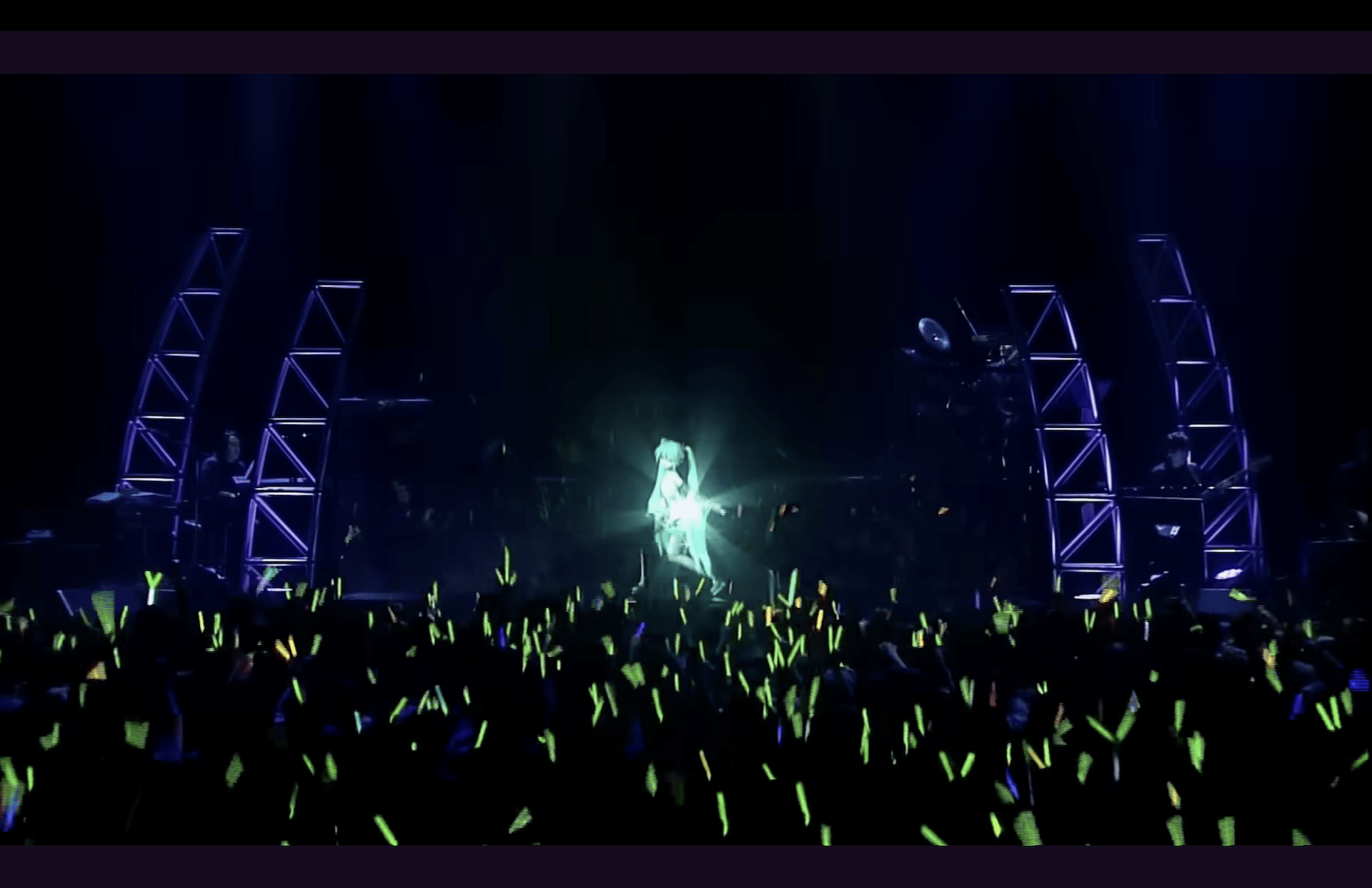

It’s appealing because it sounds interesting and distinctive and because they have potential as metaphors enriching the performance of emotion and identity. Similarly, Vocaloids the vocal synthesis software sets that were given identities and cartoon bodies (the most famous among them being Hatsune Miku) and who even became “holograms” in live concert, are not fooling anyone. Their distinctive sound is by turns cute and uncanny and they became the objects around which a participatory fan culture of users making music with them took root.

“the voice alone is powerful enough to embody a disembodied being”

But the kind of Autotune or vocal synthesis that goes unnoticed is what lies behind the panic about the technology’s ability to hide musical inability or seemingly actively “lie” about musical ability. Such panic may or may not be justified but does now seem quaint amid today’s AI technologies because all that was at stake with Autotune is someone’s ability to pitch correctly. At stake with AI-generated audio is every aspect of the vocal performance and the musical accompaniment as well. In her set of reflections ‘13 Way of thinking about AI’ (highly recommended), Jennifer Walshe points out that accurate modelling of the human voice has been historically difficult, not least because we are usually so attuned to its subtleties. Whether or not we agree that AI has cracked the problem (the trained ear can still often tell when a human voice is AI-generated) or will do in the future, it has gotten closer than ever before to being able to, as Walshe puts it, ‘serve the one thing which generative AI cannot – a body,’ potentially allowing it to ‘serve gender expression, age, class, ethnicity, body type, ability.’ What’s more, ‘it doesn’t matter whether the “image of the body given” to the listener exists in physical space. Fandoms have evolved around virtual idols and influencers like Hatsune Miku and Miquela, because the voice alone is powerful enough to embody a disembodied being.’

Serving the body entails more than just serving its sounds. In the same way that technology doesn’t just help us make signifiers but is itself a signifier, listeners are interested in human bodies not just because of the way they sound but because, somewhere along the chain of social and technological mediations, they represent people and their activities. Listening is not just sonic, it is social. The ‘people’ represented can be partly metaphorical or imaginary and might not have a physical body, as is the case with Vocaloids or cartoon characters. But even with Vocaloids and cartoon characters, there is often the remote but significant awareness that human activities are behind the scenes. Listening to songs composed for Hatsune Miku, one is not just hearing Hatsune Miku as a character but the people who have invested time and effort into her. Watching old Warner Brothers cartoons, one is not just hearing Bugs Bunny the amusing character but the voice actor Mel Blanc, one of the greatest vocal performers of his era. But even anonymously or distantly, listening involves a sense of social presence and its implication: someone is there, doing something. Not only that, but many of us prefer it if that someone is being paid or otherwise respected, and in some cases AI is the sound of real people whose work has been exploited, even if they have been occulted somewhat by the technology’s statistical processes.

“Listening is not just sonic, it is social.”

So the question is not whether AI music involves people or not. AI music involves both imaginary and, somewhere along the line, real people. The question is whether AI needs to and can viably serve people—imaginary, real, or both—in a given instance. I mean the word ‘serve’ here both in its sense of ‘provide’ (as in serving a meal or serving face) and in its sense of ‘be a servant of.’ Put another way, when listening to AI music, evaluate not just whether it sounds good but whether it is putting you in contact with people and whether people are being respected, and in both cases ‘people’ includes both you the listener and the people you’re listening to.

Let’s take an example of a given instance of AI vocals in music. Caribou’s latest album Honey was released in October of last year and while that act has performed live as a four-piece, Honey’s Bandcamp page says ‘All songs produced and recorded by Dan Snaith.’ It doesn’t specify the use of AI, but many of the album’s reviewers understood its vocals to have been AI-assisted: Snaith recorded his own voice (as he has done before) but this time used AI to alter it in various ways to suggest different people with different vocal timbres and ranges. In a contemporary update on how the vocoder works, Snaith imposed statistical models of other people’s voices onto his own.

To my ears, it’s difficult to tell, if you don’t already know, that Honey’s vocals are using AI. It’s clear that the voices are technologically mediated, but that’s par for the course for the kind of music Honey is. It’s an electronic album that broadly evokes club musics, and as such while the vocals may be AI-assisted, they do work in context, slipping relatively comfortably into house, garage and techno traditions of voices sampled, chopped and edited into dance beats. In fact, the album uses traditional vocal samples as well, crediting them in the text accompanying the album. And since the vocals are often filtered or just one element in the album’s often thick textures, there’s less chance that they’ll fail to stand up to sonic scrutiny, too.

Nor is the album engaging self-consciously or conceptually with AI. While many parts of the album reminded me of Darkstar’s ‘Aidy’s Girl’s a Computer,’ a club tune popular in London in the late 2000s, that tune is self-conscious about technology in three ways. Firstly, its title lets you know that this is a tune about computers. Secondly, listeners further investigating the tune may come across the story about how the song got its name—that it’s a response to one of the duo’s attempts to make their computer speak—which may inform the way they listen. Thirdly, the glitching of the voice in ‘Aidy’s Girl’s a Computer’ lets you know that you’re listening not just to a voice, but to a technology. Honey, on the other hand, doesn’t especially signify the technology, and doesn’t really cue the listener into thinking about the technologies involved, doing so faintly, if at all.

Rather than a conceptual interrogation of AI, then, Honey simply uses it as electronic dance music has always done: a solo producer sampling vocals and riffs into a musical flow. And we survived that didn’t we? Well, precedent doesn’t make everything OK, doesn’t mean that the music is serving people. The posthuman divas of electronic dance music are undeniably alluring not just sonically but socially too, because they serve glimpses of the body and its meanings in a transcendent setting. But that doesn’t mean the people whose voices were sampled were being paid, credited or entirely respected. One of the more famous cases is the sampling of Loleatta Holloway in Black Box’s 1989 single ‘Ride on Time.’ The insensitivities might be cultural as well as material, such as when Islamic calls to prayer are heard on dancefloors. And unfortunately, on Honey’s track ‘Campfire,’ we hear rapping from a voice that will be heard as Black American, situating this 2024 album in the long history of appropriation of the sounds of Black people without particularly crediting them (something musicologist Matthew Morrison has termed ‘Blacksound’), going back through ‘Ride on Time,’ through Elvis, and to blackface minstrelsy.

“It seems that for now, at least, AI as a signifier simply belongs to the dehumanizers rather than the humanizers”

One might say the immediacy and practicality of AI is a factor here. I can’t say whether Caribou was financially in a position to pay human vocalists, or even whether working with them might have hampered the immediacy of Snaith’s creative process somehow. But one can at least say that Caribou, an established artist, isn’t some kid without the money or chops to work with a vocalist uploading their tunes to Soundcloud. Sometimes people refer to music technologies as ‘democratising,’ but if there’s a redistribution of musical power to the people to be had with AI, Caribou might not be the producer who’s most in need of it. Listening to Honey the effect is less of technology serving a new and intriguing social connection between people mediated by sound, or something being presented and engaged with critically, than the sound of someone cutting corners.

Perhaps Honey is a sign of things to come, and as time goes by people will know or care less and less about whether an electronic dance track has AI vocals. It would be a benefit if it allowed more people to produce and listen to interesting music, though it would be a shame if vocalists were exploited, went unpaid, or gave up on music altogether. But there’s also the backlash against AI among the left and people interested in and employed by the arts, which has been getting vociferous. In some contexts it’s a serious faux pas to use or even post an AI image, even as a joke. The climate case for not using AI is enough by itself, but the fact that AI image generation has helped itself to the visual style associated with well-known computer-critic Hayao Miyazaki, and that it has been used by the Trump administration to depict deportations is not helping. It seems that for now, at least, AI as a signifier simply belongs to the dehumanizers rather than the humanizers, in the same way that, in the West at least, the swastika is no longer a symbol of positivity associated with Eastern traditions. Perhaps AI now belongs to those who use it not because they respect people and want to critically engage with technology in a social context, but because they do not respect people.

Maybe all is not lost, however. To return to the vocoder: it would be facile to look at Kraftwerk performing as robots and to hear their vocoder and interpret it all as the dehumanization of music. What they’re playing with is the dehumanization of people and the humanization of technology. In a moment of breaking character, Kraftwerk’s Ralf Hütter said that the aim of the band’s album Computer World was ‘making transparent certain structures and bringing them to the forefront… so you can change them. I think we make things transparent, and with this transparency reactionary structures must fall.’ Whether it happens in the music or around it, the role of AI in art and society as a relationship between people (whether positive or exploitative) should be made transparent as often and as thoroughly as possible.

About the author: Adam Harper is a music critic and musicologist currently working as a lecturer at Christ Church and St John’s Colleges at the University of Oxford. His work investigates the role of technology in the production and meaning of music in both contemporary and historical settings. He has written for Wire, Resident Advisor, The FADER, Dummy, and Frieze, blogged at Rouge’s Foam, and is the author of Infinite Music: Imagining the Next Millennium of HumanMusic-Making(Zer0 Books, 2011), which rethinks the ontology of music in the context of contemporary musical possibilities. He has given talks on music at CTM, Unsound, Berlin Music Week, Donaufestival and more. He is currently working on a study of the meanings of electronic audio oscillators intwentieth-century music and audiovisual media.

This article is brought to you by Struma+Iodine as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.